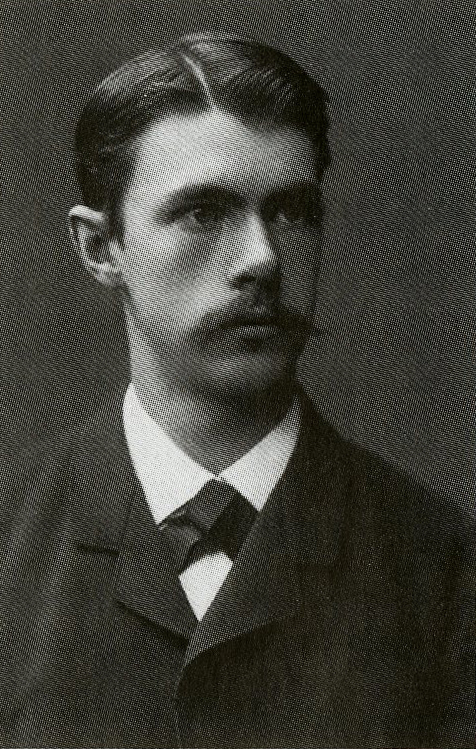

Carl Nobel, Ludvig’s second son, was born in St Petersburg in 1862. At the age of 25, he took over responsibility for Ludvig’s machine-building factory and became a well-liked and successful manager of the factory, which also meant that his father’s debt to Alfred Nobel could be paid back.

To get to know Branobel, which had its head office in St Petersburg, Ludvig took Carl along on a long visit to Baku and the Caucasus in 1884. There they stayed in Villa Petrolea where they felt at home in the Finnish-Swedish colony. Carl wrote to his younger sister Anna about what were to him exotic people in a dramatic landscape.

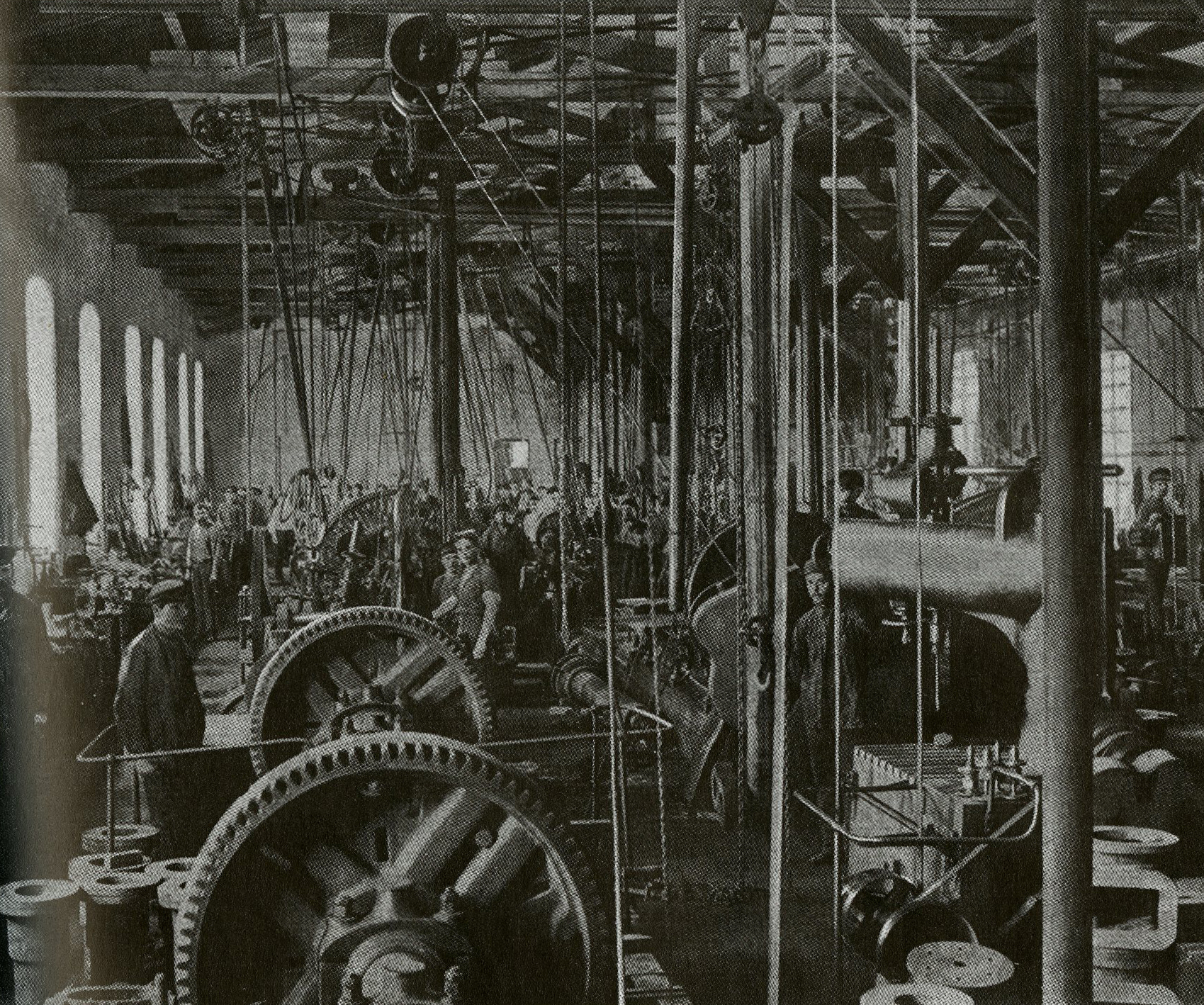

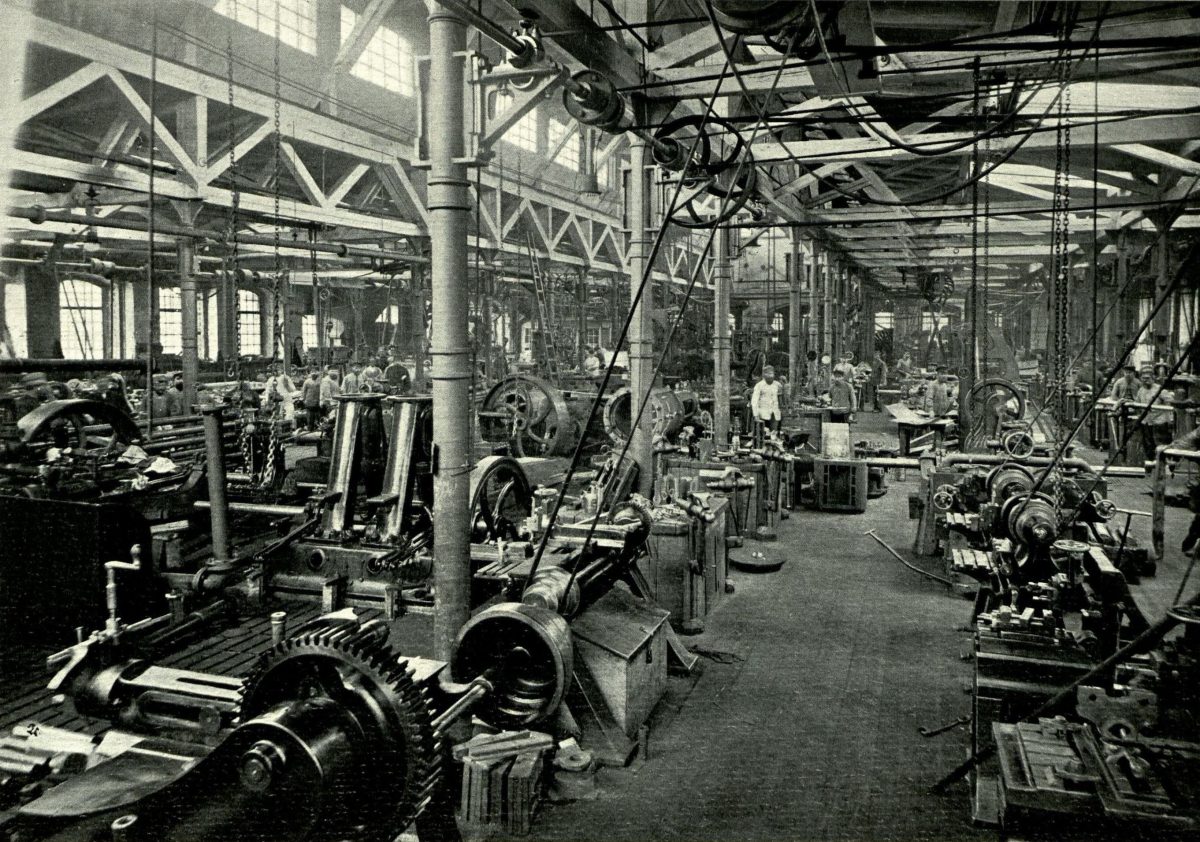

The years after his father Ludvig’s death in 1888 were characterised by a need for specialisation in the manufacturing industry, as competition was growing due to the worsening times. For Ludvig’s son Carl, this meant greater responsibility for Ludvig Nobel’s machine-building factory.

Card had studied at the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm and had been in contact with Swedish industry, including de Laval’s cream separator. Ludvig Nobel’s machine-building factory became de Laval’s representative in Russia. In the beginning, the heavy parts were manufactured in St Petersburg while the light parts were brought from Sweden. The separator was then imported as a whole from Sweden while repairs were carried out at the machine-building factory in St Petersburg. The turnover increased from year to year, and in 1903, two of Ludvig Nobel’s sons, Emanuel and Emil, together with de Laval Separator, formed the trading company Ludvig Nobel, which was converted in 1908 into AB Alfa-Nobel.

Ludvig Nobel had obtained the rights to sell his brother Alfred’s dynamite in Russia. Carl confirmed in a letter to his uncle Alfred that the interest on the loans to Disconto Gesellschaft in Berlin, Sven Carlsson in Warsaw and Alfred himself ate up the profits from the dynamite sales and factory. Carl therefore wanted to issue new Branobel shares for three million roubles. Carl had noticed that many were inclined to buy and that even interested parties abroad had confidence in ‘our business after they had seen the enormous spread and sale of petroleum’. The business did well after that and the debt to Alfred from 1882 could be paid back.

Carl corresponded keenly with his uncle Alfred, asked about the sale of shares and commented on his successes with Alfred’s smokeless gunpowder ‘that had become well known in the civilised world’. He wanted to report the official records from the test shootings in military magazines, and he expected great interest from possible manufacturers that wanted to offer the gunpowder to the Russian government. ‘Patent [the gunpowder] in Russia!’ Carl urged. ‘We thank Uncle for all the kindness he has shown us and we shall understand and appreciate it, not just in words but also in principle!’

Carl Nobel devoted great interest to steam engines. He employed the eminent Swedish designer Sixtus Peterson, who produced a triple steam engine for the factory’s central lighting unit, which was noted for its cost-effectiveness and beautiful shapes.

Later, Carl began to manufacture internal combustion engines, an area that would soon become the most important one. Foreign factories had designed engines to run on paraffin. The Nobel machine-building factory, with its close links to the oil industry, followed the development with great interest of the new power engine that could turn oil directly into mechanical energy. Carl acquired the right to produce these engines from a company in Switzerland, and in 1892, production started of a series of internal combustion engines with 3, 5 and 7 horsepower. At the world exhibition in Chicago in 1893, the factory was able to exhibit engines intended for small plants. The engine was later adapted to run lighting tanks for the Russian army.

Carl Nobel died of diabetes at the Bellevue Hotel in Zürich in 1893. The factory lost a conscientious and considerate director who left a big void. His brother Emanuel Nobel, head of Branobel, took over the leadership of the factory at a time of recession, but he was overburdened with work. The younger brothers Emil and Gösta were not yet able to take over responsibility and the factory lacked real strength of leadership, wrote the Swedish engineer Anton Carlsund in a story about the Ludvig Nobel machine-building factory.

The cream separator sold well in Russia and the turnover for Ludvig Nobel’s machine-building factory increased from year to year. As a result, in 1903, Emanuel and Emil Nobel, together with AB Separator, formed the trading company Ludvig Nobel, which was converted into AB Alfa-Nobel in 1908.

(more info)

Through Carl Nobel’s contacts, Ludvig Nobel’s machine-building factory became Laval’s representative for the cream separator in Russia.

(more info)

Carl was Ludvig Nobel’s second son and took over responsibility for Ludvig Nobel’s machine-building factory at the age of 25.

(more info)