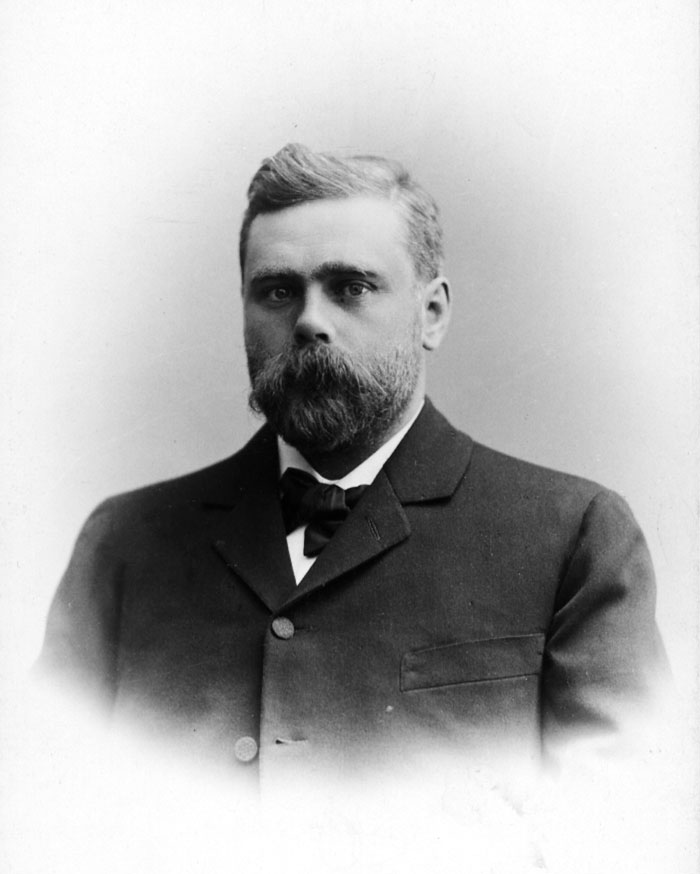

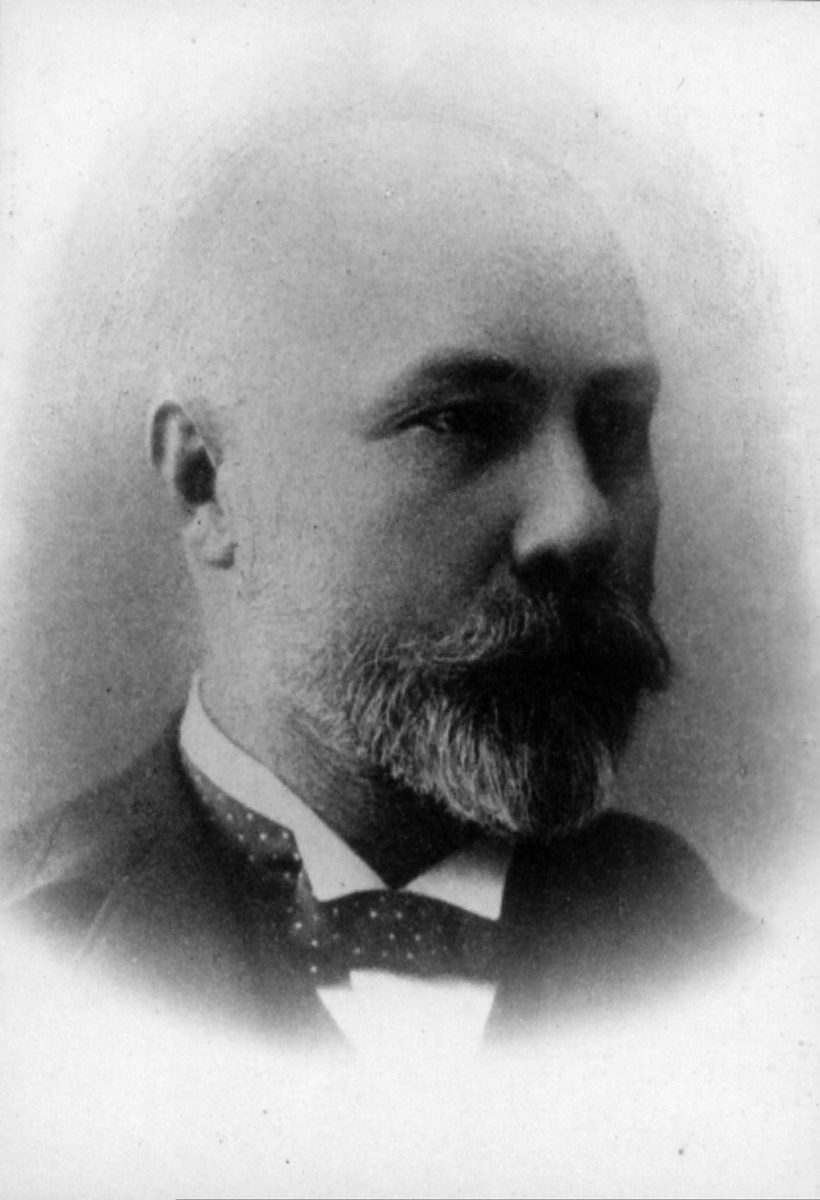

Emanuel Nobel is 28 when his father Ludvig dies and Emanuel takes over the running of the oil company Branobel. His uncle Alfred was initially doubtful of Emanuel’s leadership ability, but his nephew developed as a business leader and made Nobel’s company flourish. With the Russian Revolution and the nationalisation of all private property, however, everything is lost and Emanuel is forced to flee the country in 1918.

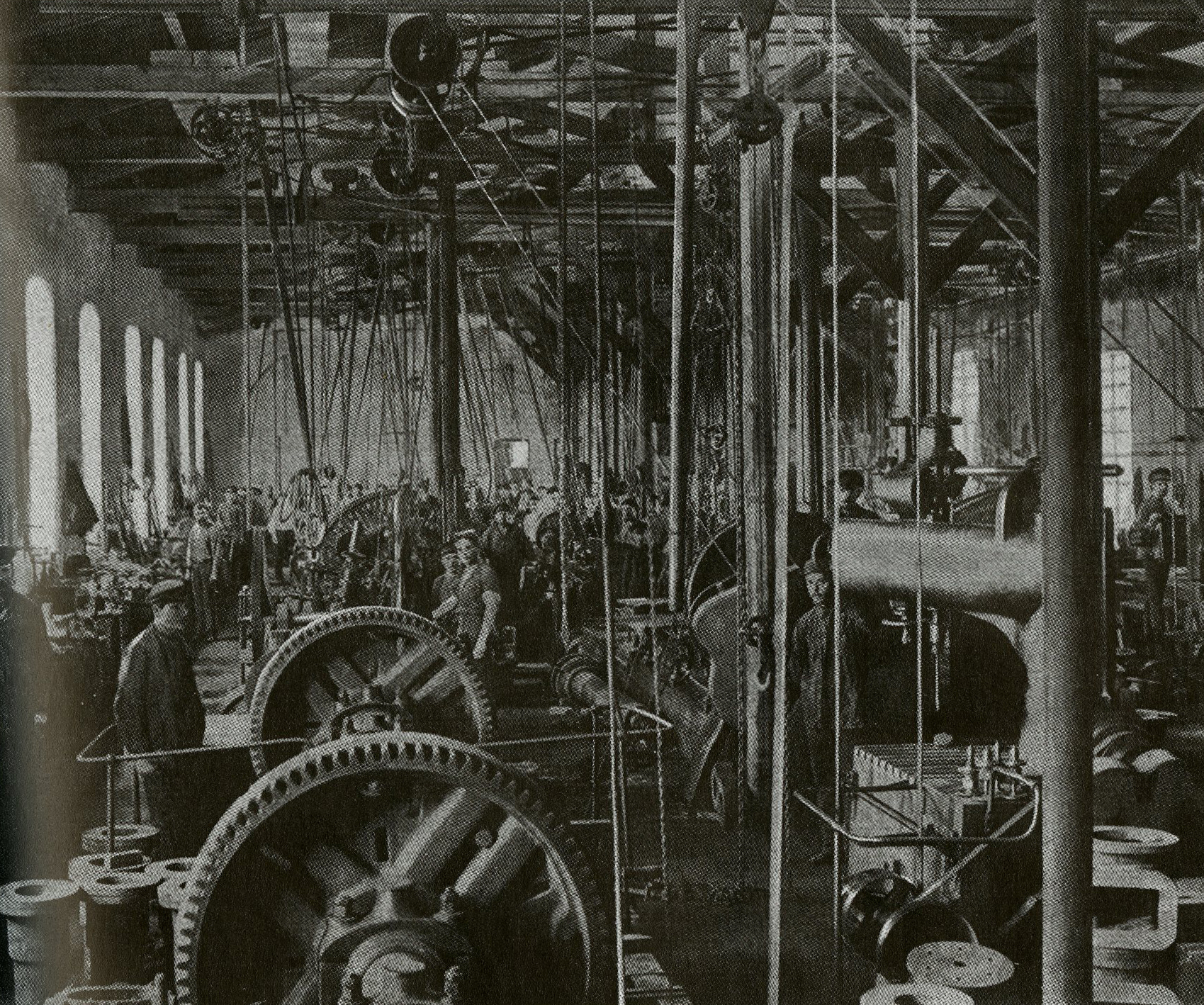

Emanuel Nobel was born in St Petersburg in 1859. After the death of his father Ludvig in Cannes in 1888, Emanuel takes over responsibility for Branobel, and his brother Carl who is three years younger takes over the machine-building factory Ludvig Nobel.

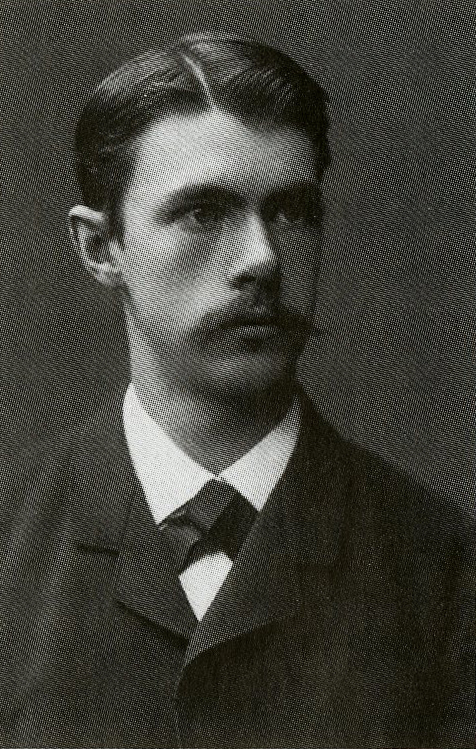

A few days before Ludvig’s death, Emanuel transferred half a million roubles to his uncle Alfred as a precautionary measure and security for the million roubles that Ludvig owed Alfred. Emanuel feared that all the assets might be locked up in a drawn-out winding up of the estate. Emanuel was given great responsibility at a young age for the companies and became sole director when his brother Carl, who was three years younger, died of diabetes in 1893 at the age of just 31.

Alfred Nobel had been a shareholder in Branobel since 1879. In his correspondence with his eldest brother Robert, we can follow Alfred’s worries over the management of Branobel. Alfred wrote that ‘Emanuel [Ludvig Nobel’s son] is indecisive. If I knew a really suitable person I would force him on the company as MD. Emanuel can rule – pro forma preside – but the reins must be in hands with leadership ability.’

With Alfred’s advice on business matters and Norwegian Hans Olsen joining Branobel’s management, Emanuel received the support he needed. Emanuel developed into a good business leader with able co-workers such as Wilhelm Hagelin, Arthur Lessner, Knut Littorin, Knut Malm, Michail Beliamin the Younger and Ludvig’s first son, his half-brother Hjalmar Crusell.

Emanuel became a Russian citizen in 1888 in connection with the Tsar family’s visit to Baku. He was later raised to His Excellency by the Tsar and member of the Russian Central Bank. He shared a household with Ludvig’s second wife Edla in St Petersburg and was guardian of his five half-siblings: Mina, Ludvig, Ingrid, Marta and Rolf. Emanuel remained unmarried and, in time, he became increasingly like a Russian prince, with a weakness for grand dinners and jewellery made by Fabergé in St Petersburg. It was Emanuel who carried through his uncle Alfred’s controversial will – against Alfred’s brother Robert’s family, the institutions and the Swedish King Oskar II.

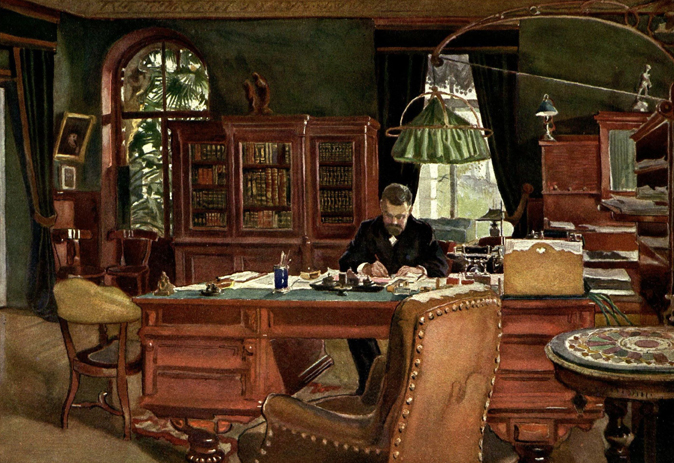

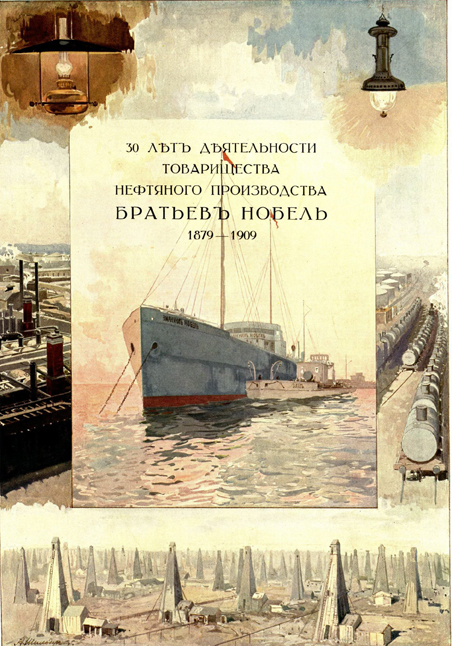

Emanuel’s 50th birthday and the company’s 30th anniversary both fell in 1909. The company was at its peak, it was well run and its profit distribution to the employees raised envy among competitors. Emanuel was Chairman of the Board in the head office in St Petersburg. He now had the power and the title, and he had polished his skills as a financier with the best possible contacts with the Russian state and the European banks.

There had been warning signs, however, in 1903, 1905 and 1907 with growing social unrest on the oilfields and in the factories. The revolution started in 1917, and the year after, all private property was nationalised by the Soviet regime. Emanuel Nobel was at the spa in Jessentuki in north Caucasus at the time. Everything the family owned was seized. Maybe Emanuel thought that the Bolsheviks would not be able to hold onto power. At the spa, he was in the company of other business leaders and aristocrats. Most things were as normal, but they lacked cash. Emanuel helped the local bank to start a banknote printing works that sold banknotes against jewellery and securities.

The younger brother Gösta Nobel’s family was near Kislovodsk. Gösta’s wife Genia had had an unpleasant visit by bandits who had taken everything they could lay their hands on. She had hidden the children on the balcony. Genia did manage to save a pearl necklace, however, that she had sewed into her corset. The Nobels were wanted capitalists, and as Emanuel was a Russian citizen he was finally forced to flee. The Nobels travelled disguised as peasants by horse and cart for seven weeks, and they were helped along the way with food and lodgings by the company’s sales agents. On 26 November 1918, they reached Berlin.

Back in Sweden, Emanuel renounced his Russian citizenship in 1918. He died in 1932.

(more info)

(more info)

(more info)

(more info)

(more info)

(more info)