In the summer of 1896, the Russian imperial couple, Nicholas and Alexandra’s coronation is celebrated with magnificent festivities, including an exhibition at which Branobel is represented. But the coronation party is surrounded by dramatic events.

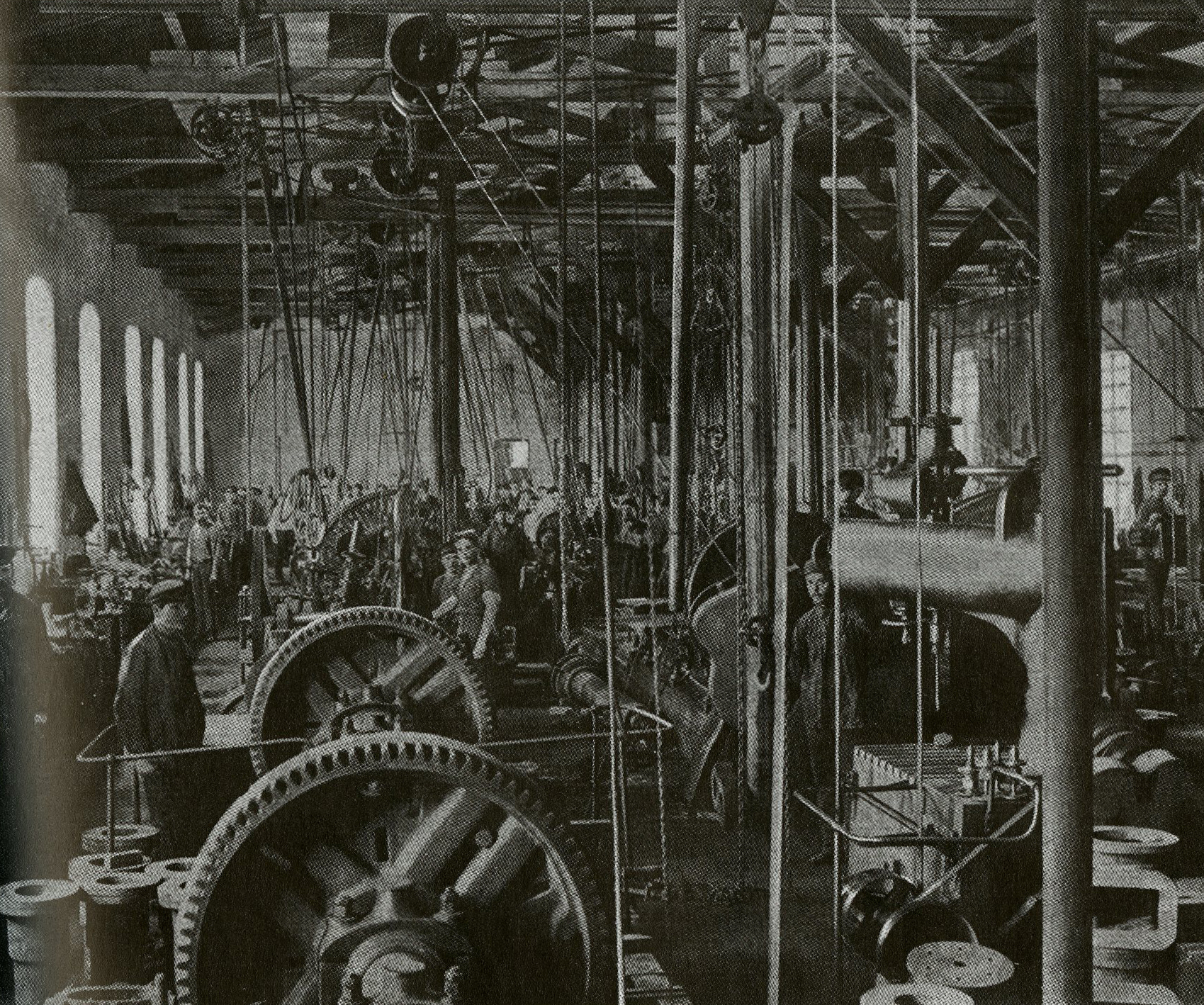

In June 1896, the Swedish engineer, Anton Carlsund, came to the pan-Russian industrial and art exhibition in Nizhny Novgorod to represent the Ludvig Nobel Engineering Works in St Petersburg.

Anton Carlsund vividly described the beautiful city, which was built on a high plateau. It stretched along the southern shore of the Oka and ended steeply at the River Volga and the old imperial fortress, the Kremlin, which was built in Byzantine style. At the traditional marketplace, the erection of impressive pavilions of various kinds was going on. Between these, wide roads, edged by flower arrangements and borders stretched out. The entire newly constructed city was a delight to the eye, according to Anton Carlsund. At the entrance to the exhibition, there were two sky-high masts that came from Siberia’s primeval forests. Between these, a strong rope was stretched and it was from this that the imperial standard with the eagle was to flutter during the couple’s visit.

The traffic on the rivers was lively and people had come from all points of the compass. The houses with their roofs painted green were embedded in leafy gardens. The gold-plated domes of churches and monasteries glittered under a cloudless sky.

The coronation ceremonies had been going on for several weeks. Following a visit to the European courts, the imperial couple were approaching Moscow. Shortly before their arrival, the foreign minister, Lobanoff, suffered a stroke and died. His dead body was part of the procession. In Moscow, large crowds of people waited. A day of public rejoicing was to take place at the Khodinka field outside Moscow and, in the name of the imperial couple, both food parcels and souvenirs were to be given out – gifts that were to be a memory for families for many generations. People queued, surrounded by barricades, and there was such intense crushing that it is estimated that 5,000 people died. The newspapers were silent, but the rumours spread to Nizhny-Novgorod.

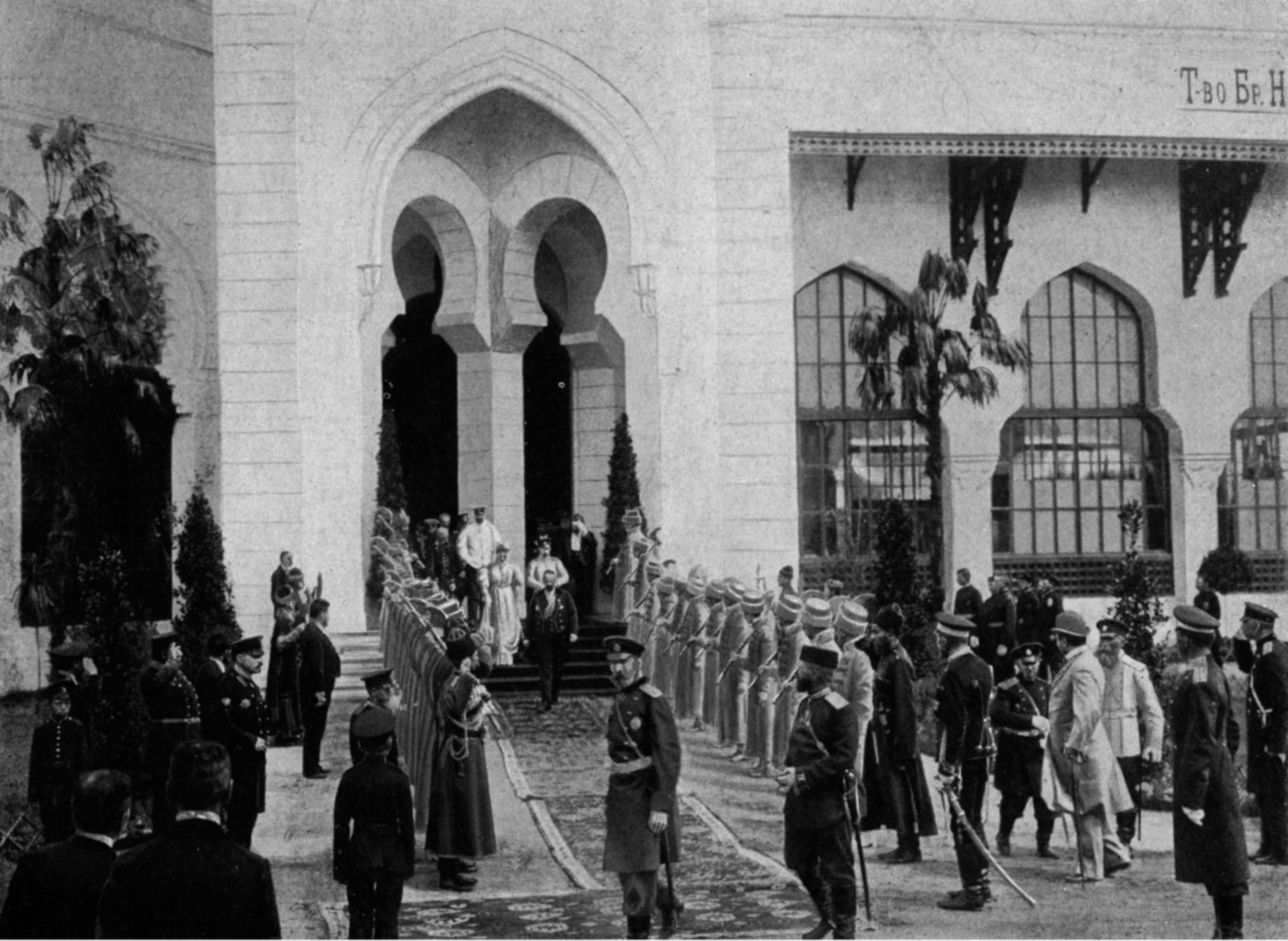

A week after the tragedy in Moscow, the imperial couple were on their way to the exhibition to see what the country had achieved most recently under the leadership of the finance minister, Witte, who had a reputation for being far-sighted. Branobel was also represented by a pavilion in the shape of a mosque. Inside, there was a panorama that showed the oil company’s plants in Baku.

Everything was in place early on the day the imperial couple was expected. The men wore full-dress uniform or tail coats and the ladies wore large toiles with lovely hats. The hours passed, the heat was terrible and the air close and oppressive. At about eleven o’clock, a few small clouds could be seen in the east and the sky suddenly darkened. It was one of those thunderstorms that usually discharge themselves across Russia’s wide steppes. The thunderstorm approached, swirling up dust, followed by lighting and rain. Everyone sought shelter. The storm came in over the exhibition area and destroyed everything in its path, Anton Carlsund tells us. Rain and hail came like a deluge from above, flashes of lightning and bangs shook the ground, the fragile buildings creaked, the roofs yielded, windows cracked, hail formed great piles between the exhibition stands of textiles and luxury items. The whole event lasted only a few minutes but caused total devastation.

”What does this mean?”, Carlsund heard an old Russian exclaim. ”This is the third sign. First the foreign minister dies at the imperial procession, then people are trampled to death at the Khodinka field and now the imperial flag is torn to shreds. How will it end for this emperor?” The exhibition area was restored in 24 hours and the imperial visitors arrived the very next day.

The mishaps at the coronation in 1896 were really an omen. The final act of the drama unfolded one night in July 1918 in a cellar in the house in Jekaterinburg where the Tsar and his family were being kept hostage. They were shot and their bodies burned with sulphuric acid to erase all traces.

(more info)

(more info)