At the end of the First World War, the position in the southern Caucasus was complicated by many interested parties around the oil fields: Turks, Englishmen, Germans, Russian Bolsheviks and also severe antagonism between Armenians and Tatars (Mohammedans). In February 1917, the Tsar abdicates and, in June 1918, the Soviet Regime nationalises all private property.

When the Bolsheviks took over power in Baku in 1918, the heads of the private companies were allowed to remain in their positions, but were to be controlled by workers’ councils. Branobel’s managing director, the Swede, Arthur Lessner, found himself in a hopeless battle for influence over the company. He was harassed by the Bolsheviks, who locked him and a few other managers up because they refused to pay the contribution the proletariat demanded. Lessner was declared a counter-revolutionary and, according to Armenian sources, he was secretly sentenced to death. A sentence that was later changed to exile from the Baku area.

Arthur Lessner had to endure a few anxious weeks of waiting in St Petersburg until a Russian- Armenian troop, reinforced by English soldiers, suffered defeat in the war against the Turks, who captured Baku on 15 September 1918. The involvement of the English was explained by them wanting to prevent the Germans taking over the oil fields. The Turkish victors allowed their related Mohammedan Tartars to extract three days of bloody revenge on the Armenians in the city. The Azerbaijan government, which was newly formed in May 1918, was supported for a time by Turkish troops.

In August 1918, Lessner took the boat to a Baku that was free of Russian influence and Branobel was once again privately owned. The company had neither lost a lot of people or property. Lessner tells us:

The reason is that we did not have many Armenians working for us, and we also always had a good relationship with the Mohammedan population. But we were not totally without victims. Our long-standing, capable and faithful telephonist, Minas, was murdered in the company of a few other Armenians. A Turkish bomb exploded inside the factory area. One of our oldest operators was carried out badly injured from our large steam power station. A married woman, Wlassenko, had been killed by a bomb that had struck their apartment.

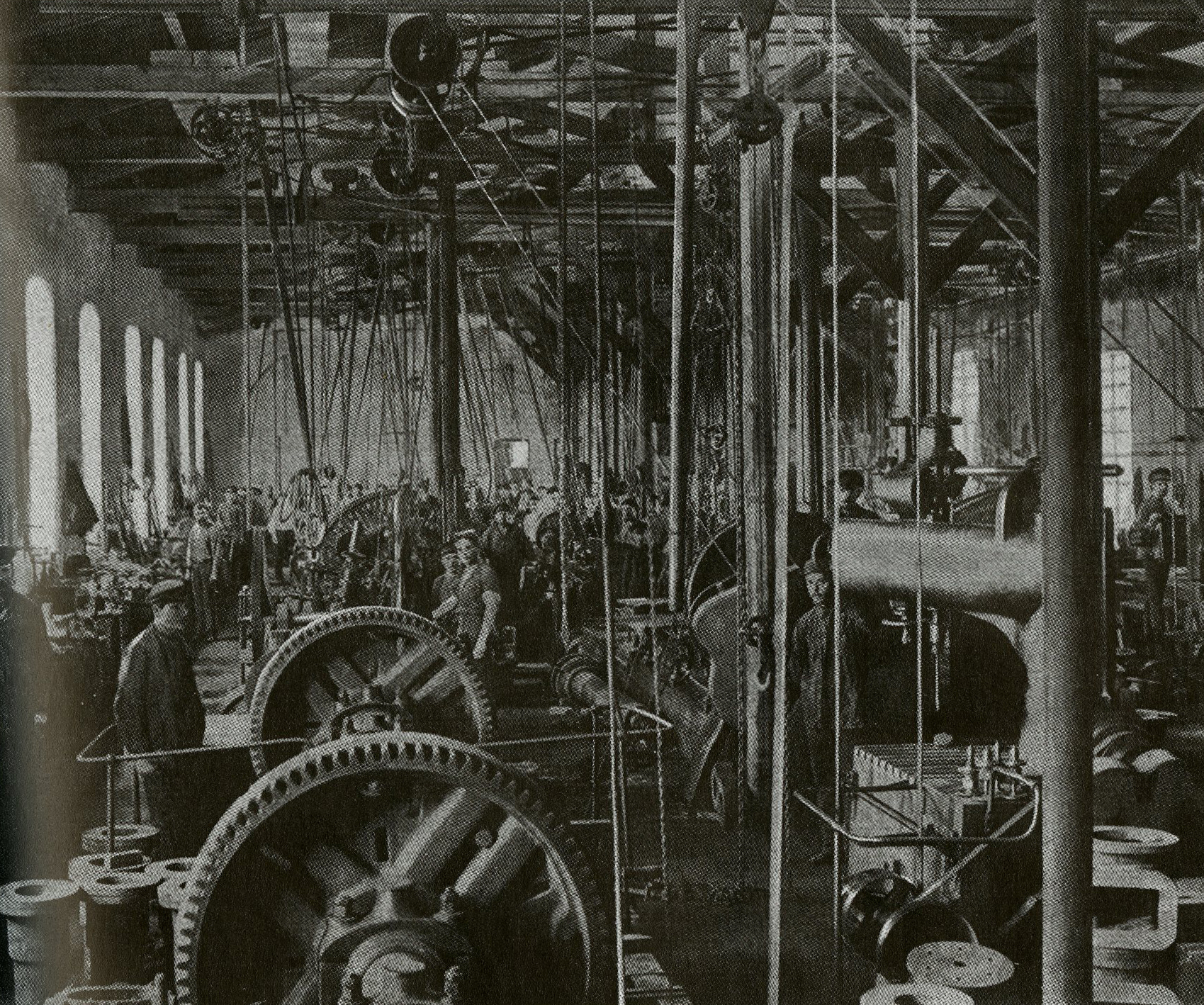

But work in the fields and the factories went slowly since there was not enough material. And then there was the question of warehousing. From August 1918, all transport from the Caspian Sea was stopped. To the north, Baku was totally cut off by the new Soviet regime – the only link to the outside world was over the commercial town of Batumi on the Black Sea. What to do with the crude oil produced – and refined products that could not be sold?

The Turks left the area at the beginning of November 1918; the English returned but left at the end of August 1919. In January 1920, a war broke out between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh, which weakened the young nation. The Azerbaijan government was convinced that they would not be able to defend themselves when the Bolsheviks began to approach Baku at the end of April 1920. They entered into peace negotiations and, on 22 April 1920, the Bolsheviks marched into what Lessner describes as for all of us such a dear city, which is still in their possession

. Now all property was again nationalised and a number of those who were reluctant were shot. No one either dared or could do anything about the Bolsheviks.

Despite this, Lessner continued to work for four months. We all did our duty in the belief that we were working for our company and that the Bolsheviks would soon be chased away

. Then, thanks to the goodwill of the senior director for the now nationalised oil industry, Serebrovsky, he was given permission to nurse his greatly weakened health in the Georgian town of Borjom and later secretly return to Sweden. Arthur Lessner was to be Branobel’s last managing director in Baku.

(more info)

(more info)

(more info)