During the tumultuous years following the Russian Revolution, the power of the communist regime rapidly spread as far as Baku. In 1920, nationalisation was the beginning of the end for Branobel. Emanuel Nobel stated that “Nationalisation is a beautiful word for a very ugly thing.” But international companies soon started doing business with the new owners.

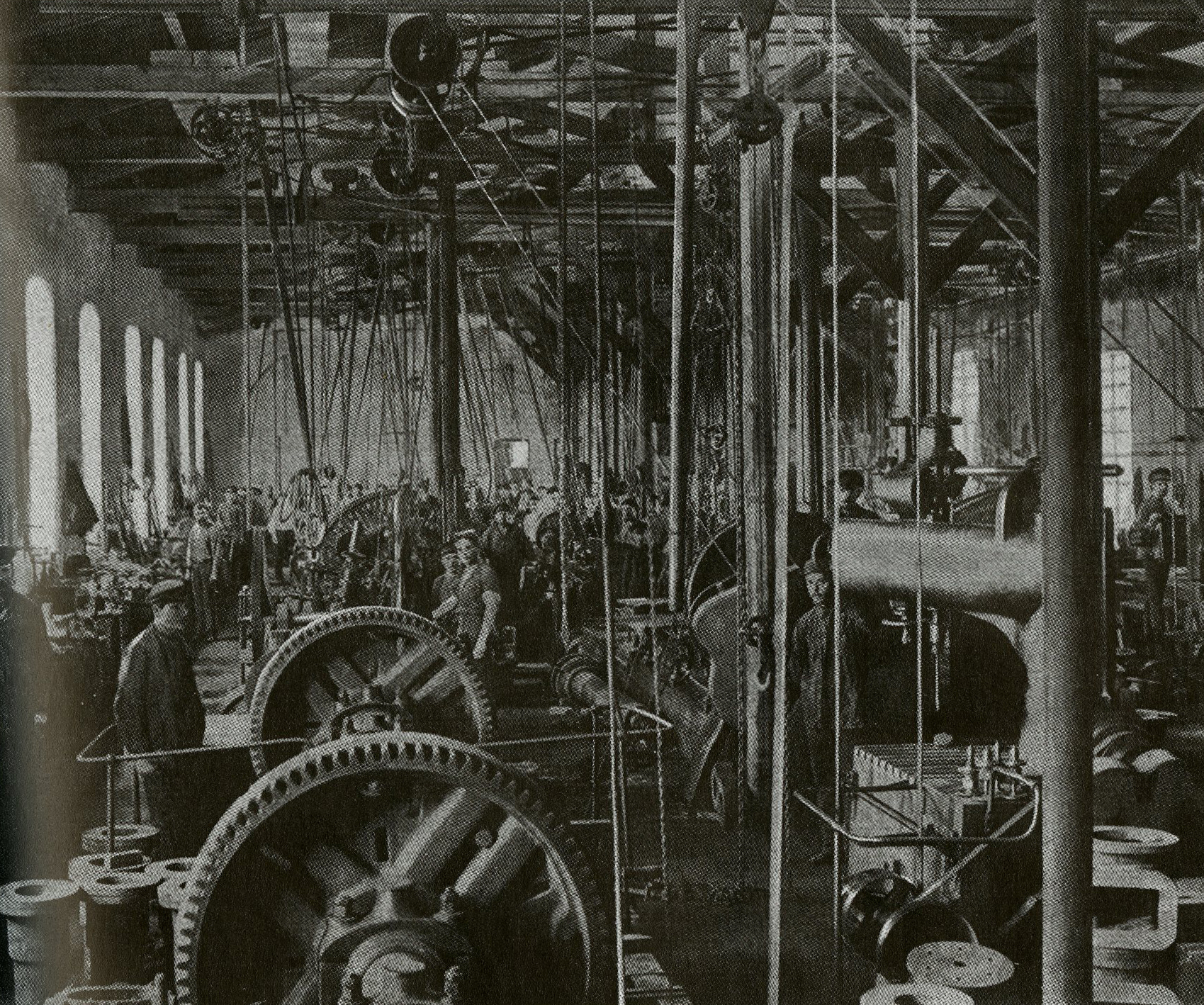

In April 1920, the Bolsheviks nationalised the Branobel Paraffin Company’s assets in Petrograd and Baku – oil field, factories, houses, shipyards, ships and depots throughout Russia. Nobel lost a number of companies of which they were co-owners: Volga-Baku, Mantashev, Moscow-Kavkaz, Votyeto Co, Brothers Mirzoiev, Aramazd, Alhan Yurt, Nefterazd, Anglo-Russian Maximov Oil Co in London and G.M. Lianosov and Sons.

In addition, Nobel was the sole owner of Vostotinoye obschestov tovarnych Skladov, (VOTS) with depots and tankers, the Rapid and Kolschida companies, I.V. Ragosin Co. and Runo Kama Shipping Co., with 13 tugs and 50 barges, and co-owner of the Cheleken Oil Company, Dagestan Co. It also had interests in fields in Grozny, Chimion, Santo and in Emba Kaspiyskoye. A whole industrial empire was lost.

Approximately two million foreigners fled to the west. Members of the Nobel family returned safe and sound to Sweden. After a year in Paris, Branobel chose Stockholm as the company’s legal domicile on 1 October 1920. Neutral Sweden was a good starting point for discussions with the countries where the company still had assets. An office was opened in the Skeppsbron district and later at Värtavägen in central Stockholm under the management, primarily, of Gösta Nobel and Ragnar Werner with Arthur Lessner, Wilhelm Hagelin and Emanuel Nobel as more occasional advisors.

The political situation in Russia was far from stable in the initial years after 1918. Standard Oil’s old dream of Russian oil and a merger with Nobel lived on. In January 1919, Standard Oil purchased eleven oil plots in Baku from the, at that time, independent government in Azerbaijan.

Negotiations to purchase half of Nobel’s investments in Russia commenced and were concluded on 30 July 1920, paradoxically enough following the Red Army’s conquest of Azerbaijan. The price was US$ 11.5 million, to be paid over two years. For Standard, this was small fry compared to the potential opportunities, but for the family it involved long-term financial security.

When Soviet Russia was threatened with total collapse in 1921, Lenin presented his new economic policy, known as NEP. The regime attracted foreign companies with oil concessions and attempted to play the companies off against each other. This was a moral dilemma for those companies that saw opportunities for good profits in Russia. Nobel, Standard Oil of New Jersey and Royal Dutch/Shell formed a “Front Uni” in 1922 under Henri Deterding as a counterweight to the calls. Soviet Russia needed to import modern equipment from the west to make headway with its own oil production. A number of companies initiated business relations with Moscow, while others could not bring themselves to deal with “those thieves in Moscow”.

When Standard Oil of New Jersey and Shell then agreed to purchase Russian oil, 5 per cent of the purchase price was set aside to support those who had lost their Russian assets. Branobel received £ 21,000 from this fund. A few years later, the cooperation ended. Baku was lost and the massive fountain in Baba Gurgur in Iraq pointed the way to new oil deposits, not so very far from Baku.

The Soviet Union was founded in 1923 and was recognised by Sweden in 1924. The Chief Negotiator and People’s Commissar for Foreign Trade Leonid Krasin purchased Swedish agricultural machinery, as well as telephone and telegraph equipment. By 1928, the Soviet Union’s most profitable export product was oil, and extraction was started with the aid of American engineers and equipment from General Electric, Westinghouse and from Sweden’s ASEA.

(more info)

(more info)