When a young Georgian engineer by the name of Sampson Mepisashvili moved from Tiblisi to Baku in 1910, the petroleum boom in the Transcaucasian region was at its peak.

The time when oil was extracted from wells by hand and transported in waterskins by horse and camel was gone. Baku was a flourishing modern town bustling with life and movement with large industrial plants and a developed infrastructure. It was surrounded by forests of oil derricks pumping crude oil through the pipelines to the refineries and further afield, from where they were transformed into a large range of oil products for the Russian and foreign markets. Nevertheless, the large-scale industrial extraction of oil needed continuous rationalization and development to be profitable.

The management and workers in the oil fields struggled against severe natural and climatic conditions that could destroy work and investments at any moment. When a new hole was to be drilled, they had to fight both against gushers and at the same time against groundwater and gas that could damage drilling operations and contaminate the oil. Since 1870, the Branobel Company had accumulated experience in drilling and many skilled engineers and technicians improved techniques during this period.

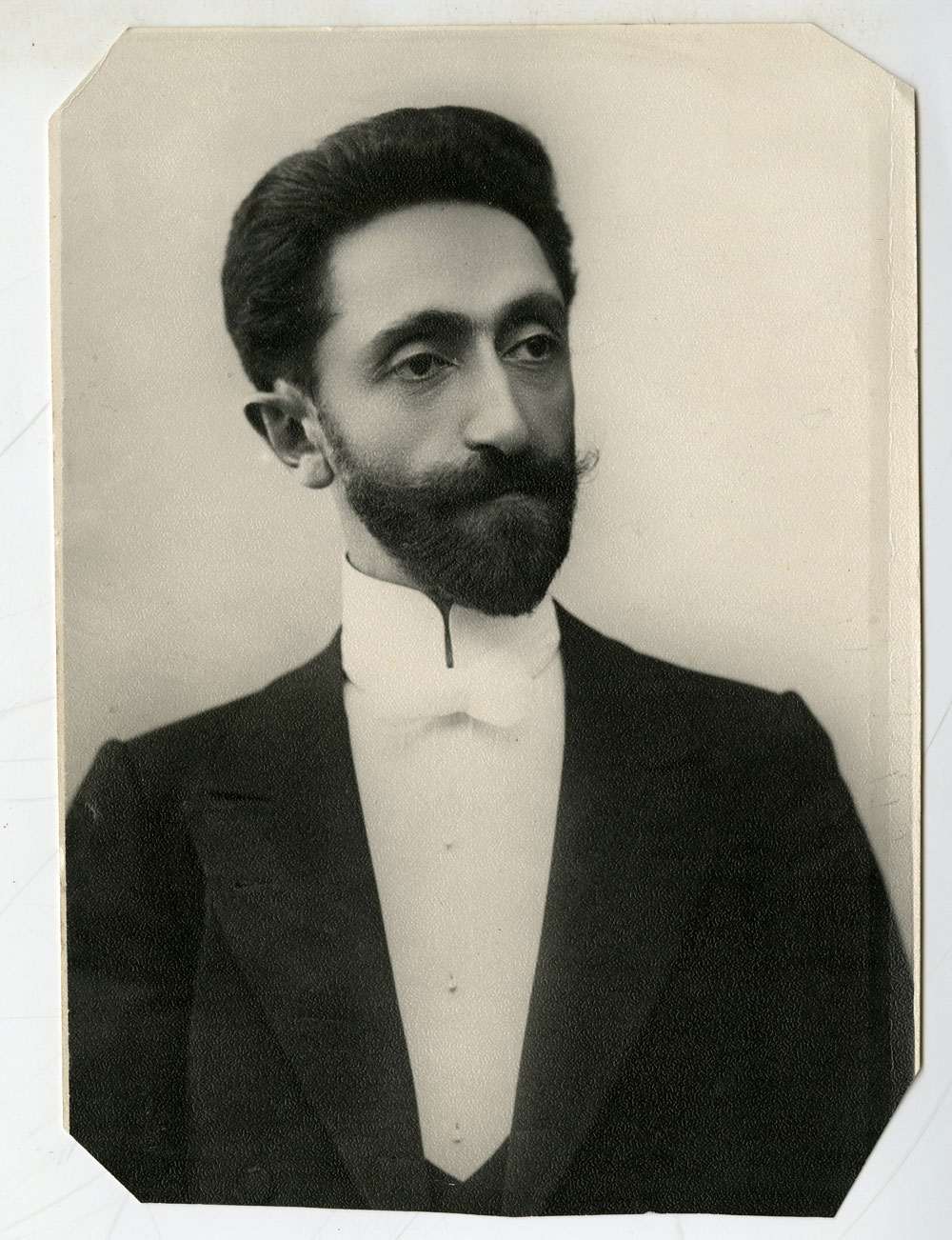

Samson Mepisashvili, or Mepisov as he spelled his Russified last name, was one of those young, innovative and ambitious engineers and inventors who got a job with the Branobel Company. He moved from Tbilisi in Georgia to Baku in Azerbaijan in 1910 and started working as drilling manager on the oil fields on the Absheron peninsula.

One of his contributions was the development of methods for sealing oil holes and oil wells. In 1914, the Technical Sub-Commission for the Support of the Oil Extraction on Balakhany district turned to Mepisov, asking him to prepare a short presentation of the most widespread conventional methods for sealing drilling holes. Sampson accepted the assignment and began collecting materials for a report. It took him three years and, just as he was finished, political development in Russia interrupted both the series of lectures as well as the actual oil drilling itself.

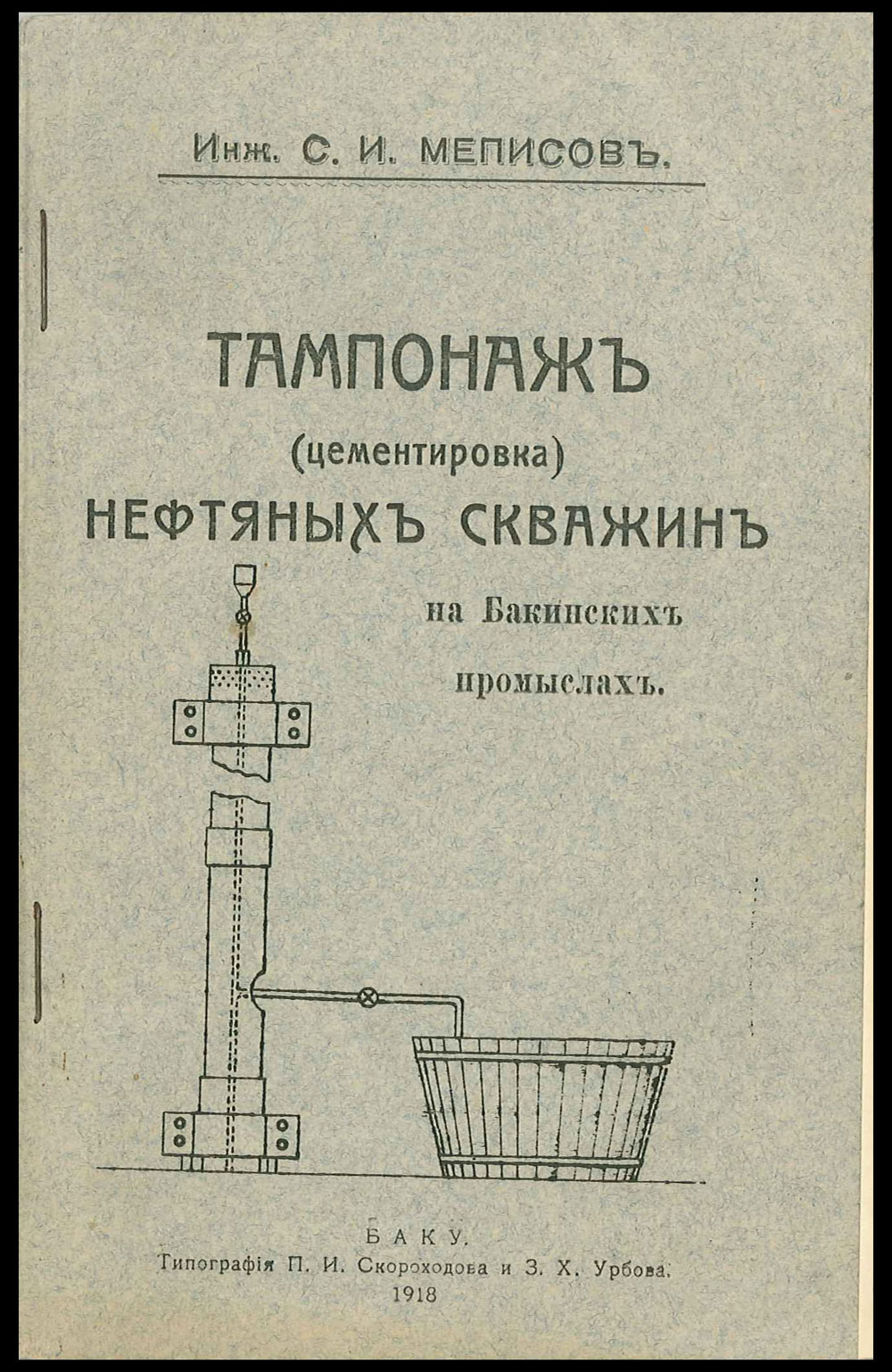

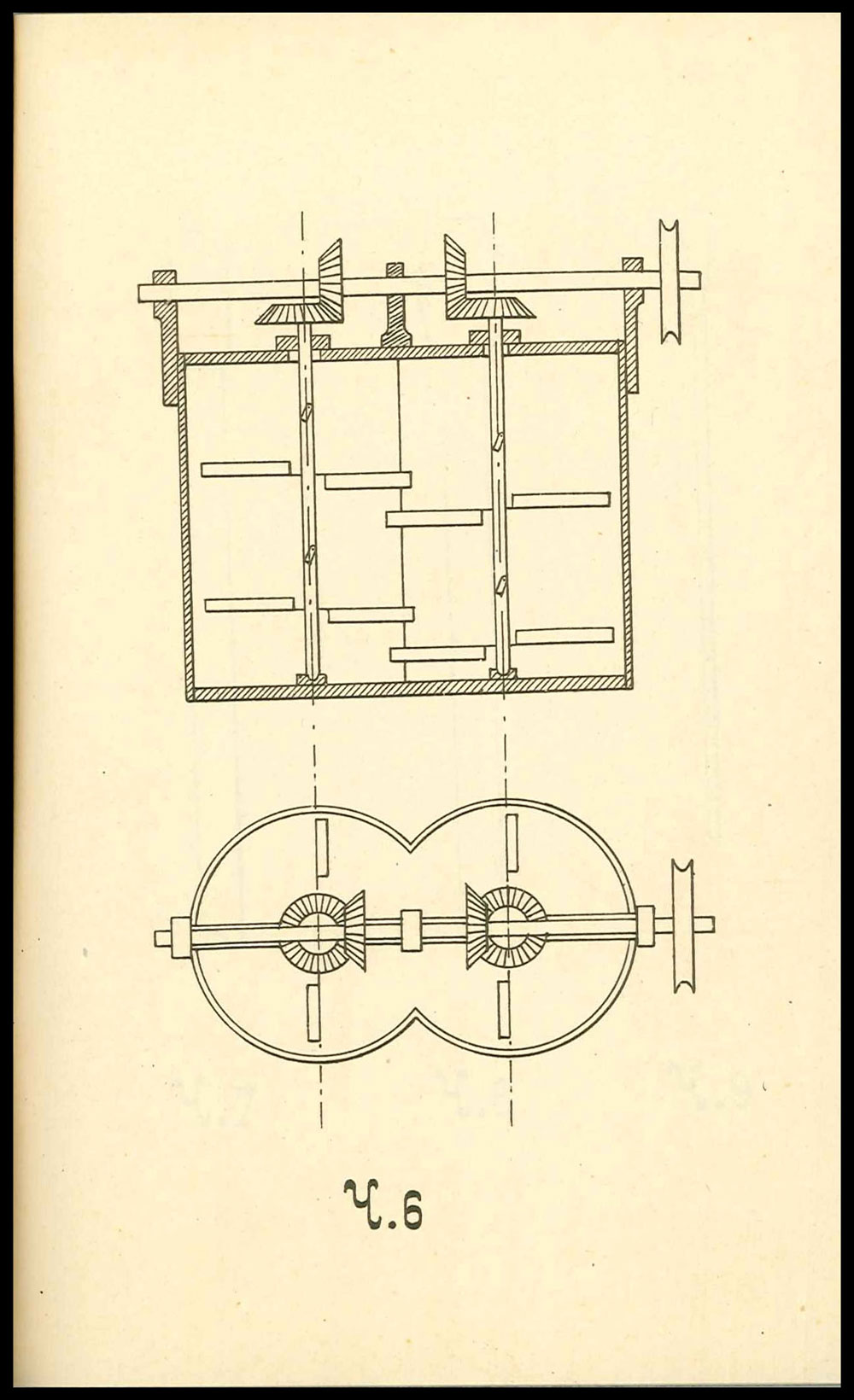

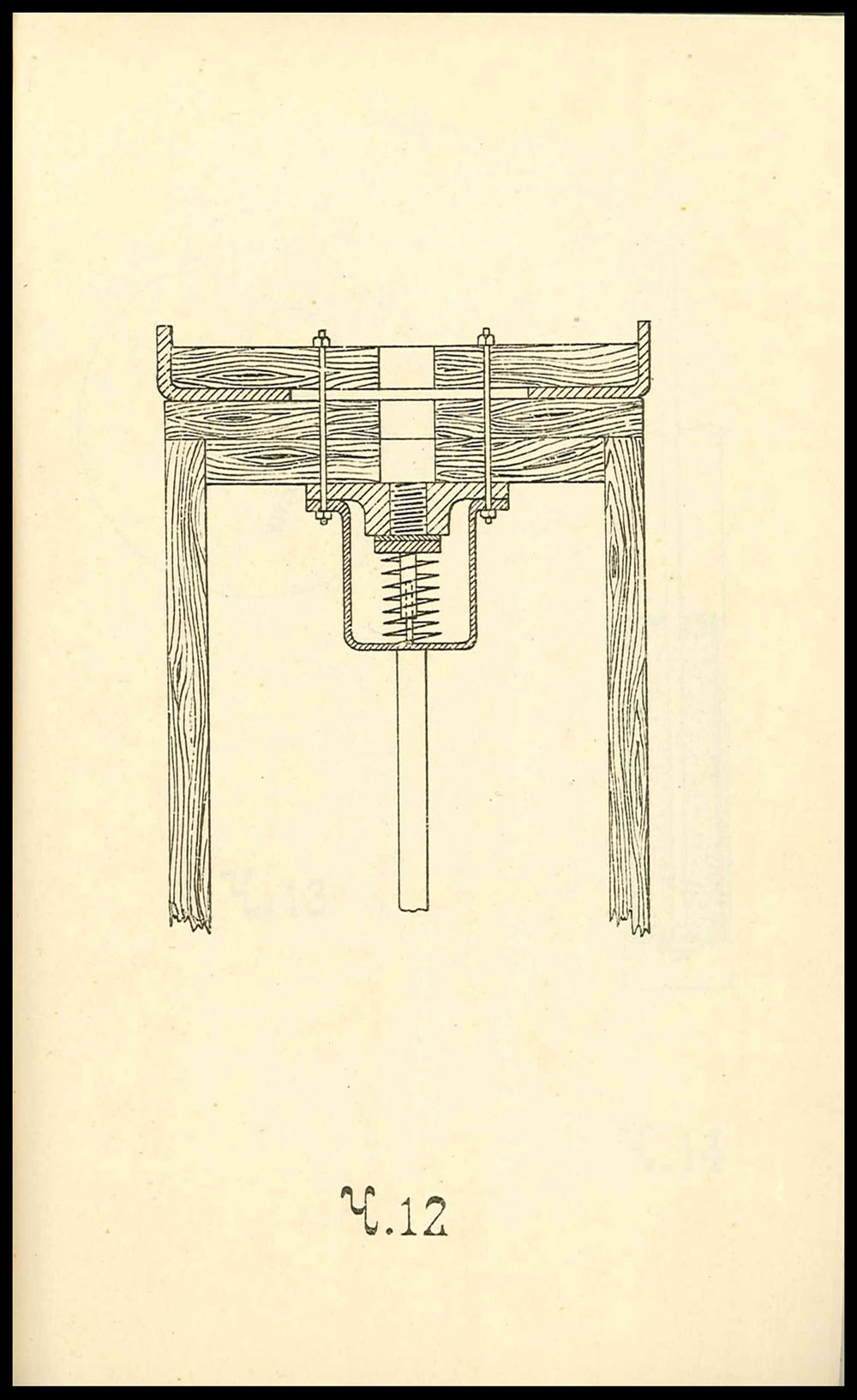

After the Turkish intervention and the proclamation of the Azerbaijani Democratic Islamic Republic in May 1918, everyday life stabilized and normal operations resumed. Oil production resumed again during the Turkish and subsequent British military presence in Baku. Sampson concluded the summary of his notes and reported his findings to the Technical Sub-Commission. The result of his work was published the same year in Baku in a small book printed by Skorokhodov & Urbov with the title Cement Sealing of Oil Wells on the Balakhany-Fields. The book contained Mepisashvili’s own sketches and drawings, showing different elements and instruments used for cement sealing the boreholes.

This tiny book contains a lot of evidence of the hard and harsh environment oil workers had to face. Mepisashvili was a talented field engineer who made observations, examined techniques, and collected and recorded performance history. He offered theories and tested various methods and he carried out calculations to come up with an optimal solution. When describing the details of sealing, its dangers and errors, and how to avoid these, he also gives us a colourful picture of everyday life at a drilling place. The description of working methods when lowering the casing pipes into the well and using various practical tricks to get the correct cement mixture in the supply pipes, or of fishing and repair operations, shows us the soiled hands, bent backs and darkened faces. We can almost hear the tired cries and curses of the workers.

The cementing of wells was a crucial stage that determined the success of the entire venture. Where the cement was delivered from, who the manufacturer was, how well or badly it was roasted, how much shrinkage occurred during transportation, and if it became wet or if it was dry, were all of vital importance.

The right sort of cement was the Portland-type shipped from central Russia and packaged in wooden barrels covered on the inside with rough paper. Austrian cement shipped in canvas bags was less effective. The sacks were not dense enough, and up to one quarter of the net weight was sometimes lost on the way. In addition, canvas bags absorbed moisture, which further reduced the amount of usable cement.

One barrel contained 10.25 puds of cement. Between 30 to 60 barrels were required for one hole, and workers had only two and a half hours before the cement started hardening.

Samson Mepisashvili was closely related to the Parnitsky family, who owned houses both in Baku and Balakhany. He led an active social life, and his two daughters eventually became eminent academics: Irina Mepisashvili in brain research and Rusudan Mepisashvili in art history. In 1920, Samson left Baku and moved back to Georgia, where he is remembered as an innovative engineer in the oil business.

The photo of Sampson Mepisashvili posing in front of oil derricks in Baku.

(more info)

(more info)

(more info)

(more info)

(more info)

(more info)