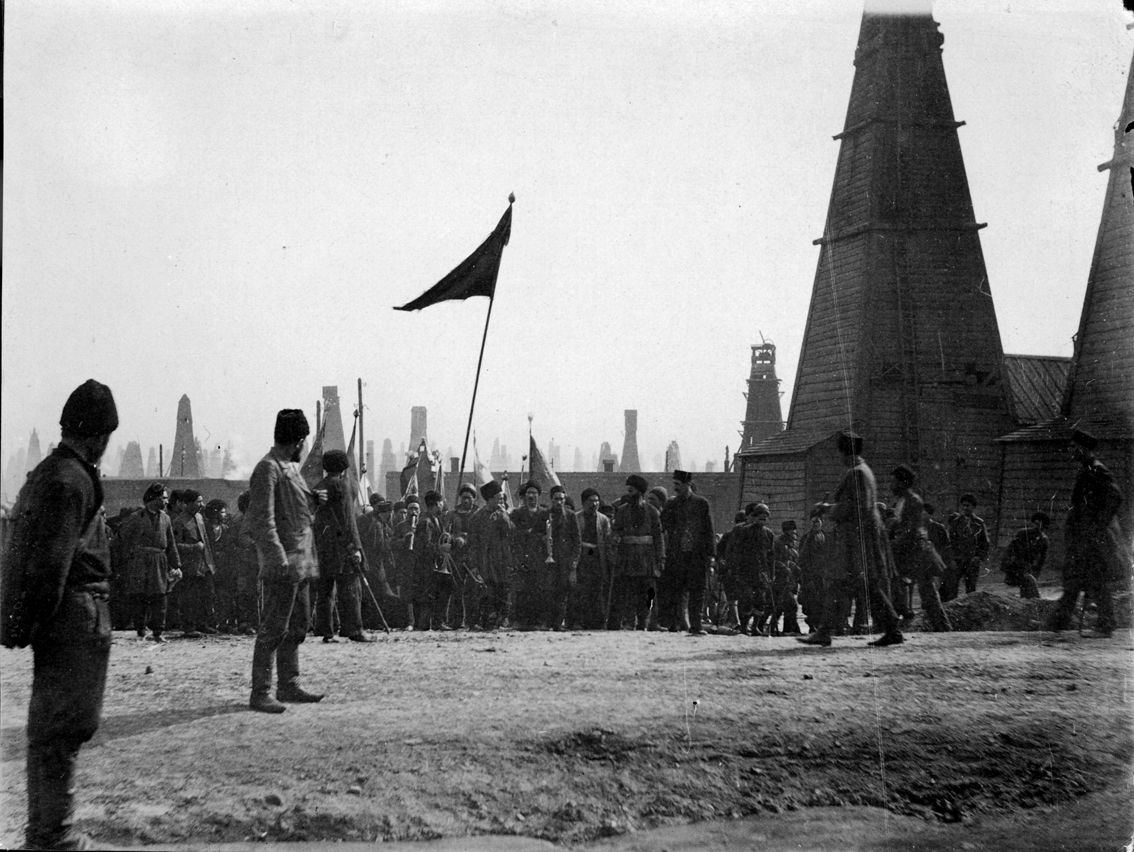

Branobel was preparing its 25th anniversary celebrations when the first spontaneous strike broke out in the summer of 1903. The background to the disturbances included the inhumane working conditions for workers in the Caucasus.

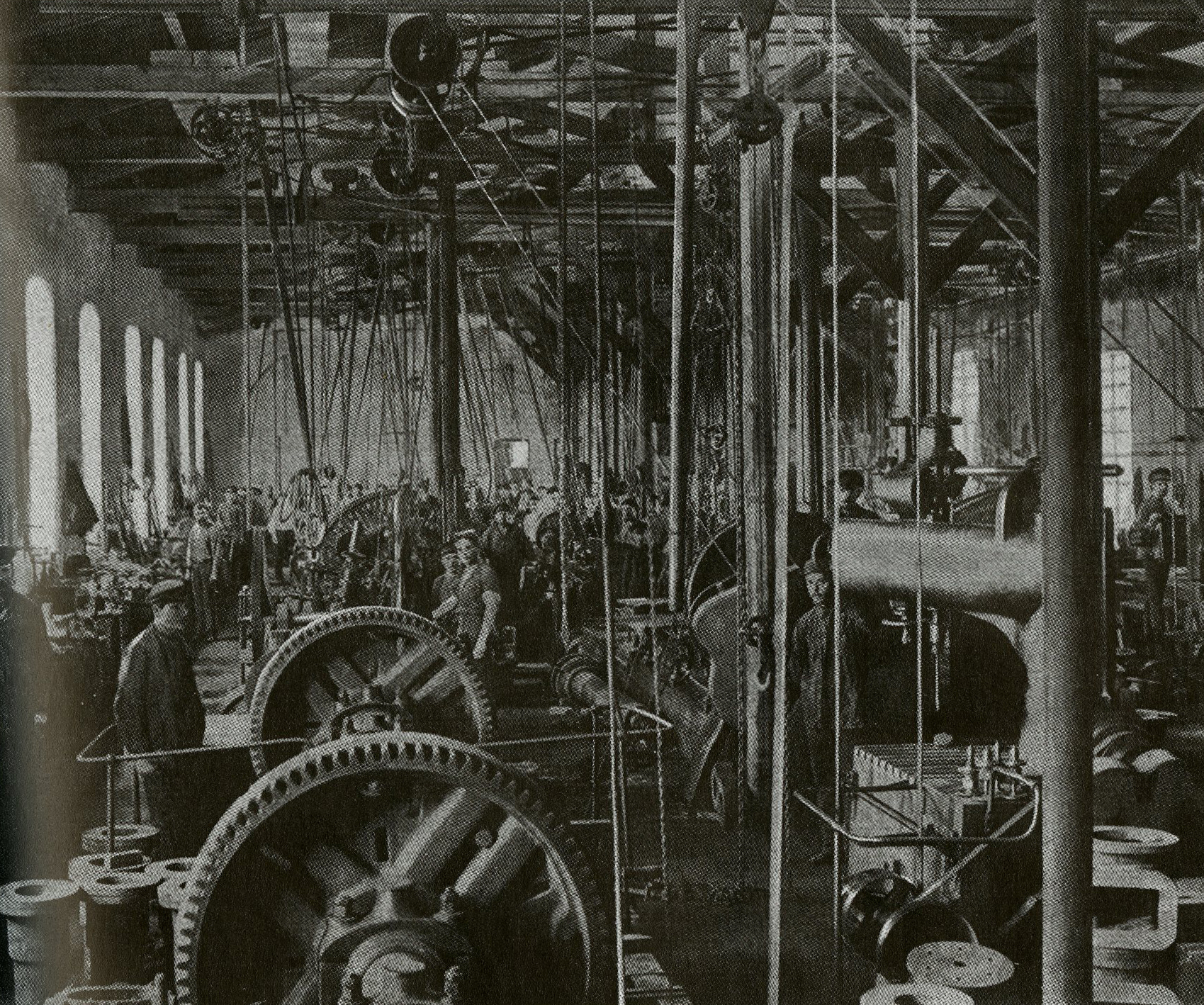

The workers in Baku, Batum and Tiflis had very poor wages, unregulated working hours, dangerous work and no compensation for accidents at work. Many of them worked alone for long periods without their families. In workshops and tobacco factories, at shipyards and oil fields, at coopers, in concourses and warehouses – everywhere the workers suffered from inhumane conditions.

In his diary, the Swedish engineer and photographer, Gunnar Dahlgren, describes how he had visited Baku’s oil district, ”The Black City” in 1906, looked into worker’s homes and been astonished at what he saw: ”Hardly any furniture or what could be called bed clothes, just dirty, grimy rags. The adults were dressed in grimy cloths and the children were practically naked. Their surroundings defied description.” The contrast with the nouveau riche oil barons’ private palaces outside Baku’s city walls, and the well-to-do residential suburb of Villa Petrolea, was striking to the city’s population and the peasants who did seasonal work in the oil industry.

The first collective agreement was signed in 1904, but concern continued and the first well-organised strike broke out in 1905. After the difficult year of 1907, the oil workers in the Caucasus had united and, the following year, negotiated the same conditions as Branobel’s employees already enjoyed, i.e. regulated working hours with eight hours at the oil fields and nine in the factories, better company dwellings or contributions to rent. Wages were paid regularly and Branobel’s employees also received a certain percentage as a bonus. Safety had also been improved and the number of accidents and fires reduced.

Branobel had – for the time – a generous personnel policy, based on the experiences of Ludvig Nobel and Peter Bilderling during the 1870s when they built up a model industry in Izhevsk in the Urals and improved living conditions for the working-class families there.

In Baku, the company had built the residential suburb of Villa Petrolea in 1882-84 for their salaried personnel with good accommodation and gardens. The lack of accommodation for the company’s workers had been an urgent matter in 1898 when Branobel leased 5.5 hectares of land in the vicinity of the Sabunchi oil field and built the new district, Na gore, ”on the mountain” with paved streets and electric lighting. Together with the housing in Villa Petrolea, there was now space for almost 4,000 employees and their families.

But, in 1903, Branobel had refused to go along with the workers’ entitlement to organise themselves or be allowed to participate in decision-making on worker issues. Now the company’s management gave in and the workers voted to form committees that would negotiate with the management so as to ”avoid misunderstandings”. The personnel received subsidised food, the bachelors were given dormitories with real beds and drying rooms for clothes, their own loan society and free medical care. The children got schools and a cooperative store with cheaper groceries. At the Nobels’ depot in Astrakhan at the mouth of the Volga, there were 2,500 employees with the same service.

But the managers at the oil-drilling fields and in the workshops were not always suitable for directing and allocating work, particularly when they were challenged by revolutionary agitators with new ideas. One of these was the Georgian, Josef Dzhugashvili, who was called Koba, later better know by the name of Joseph Stalin. He was arrested by the police and imprisoned several times and finally deported to Siberia, from where he later returned to Baku. The revolutionary passion was spread through leaflets from the secret printing house, NINA, in a cellar in Baku. Here, the magazine ISKRA (The Spark) and the Communist Manifesto were produced. Through Branobel’s widespread distribution system, banned printing matter secretly found its way out into the Tsar’s empire..

(more info)

(more info)

(more info)

(more info)