What was life like for a young Swedish woman in Baku at the turn of the last century? We can find out much about family life in Nobel’s Villa Petrolea from Ruth Grapengiesser’s frequent correspondence with her mother and sister at home in Sweden.

The newly qualified physiotherapist Ruth Grapengiesser was just 23 when she arrived in Baku to become a companion to the works manager Wilhelm Hagelin’s wife Hilda, to whom Ruth was related. She was also going to be looking after the Hagelin’s children Boris and Anna, and later the youngest Volodja.

Through Ruth’s frequent correspondence with her mother Maria and sister Ava at the Manor Norrby in Sweden, we can follow Ruth’s life as a young woman in St Petersburg and Baku, and later as a mother to several children.

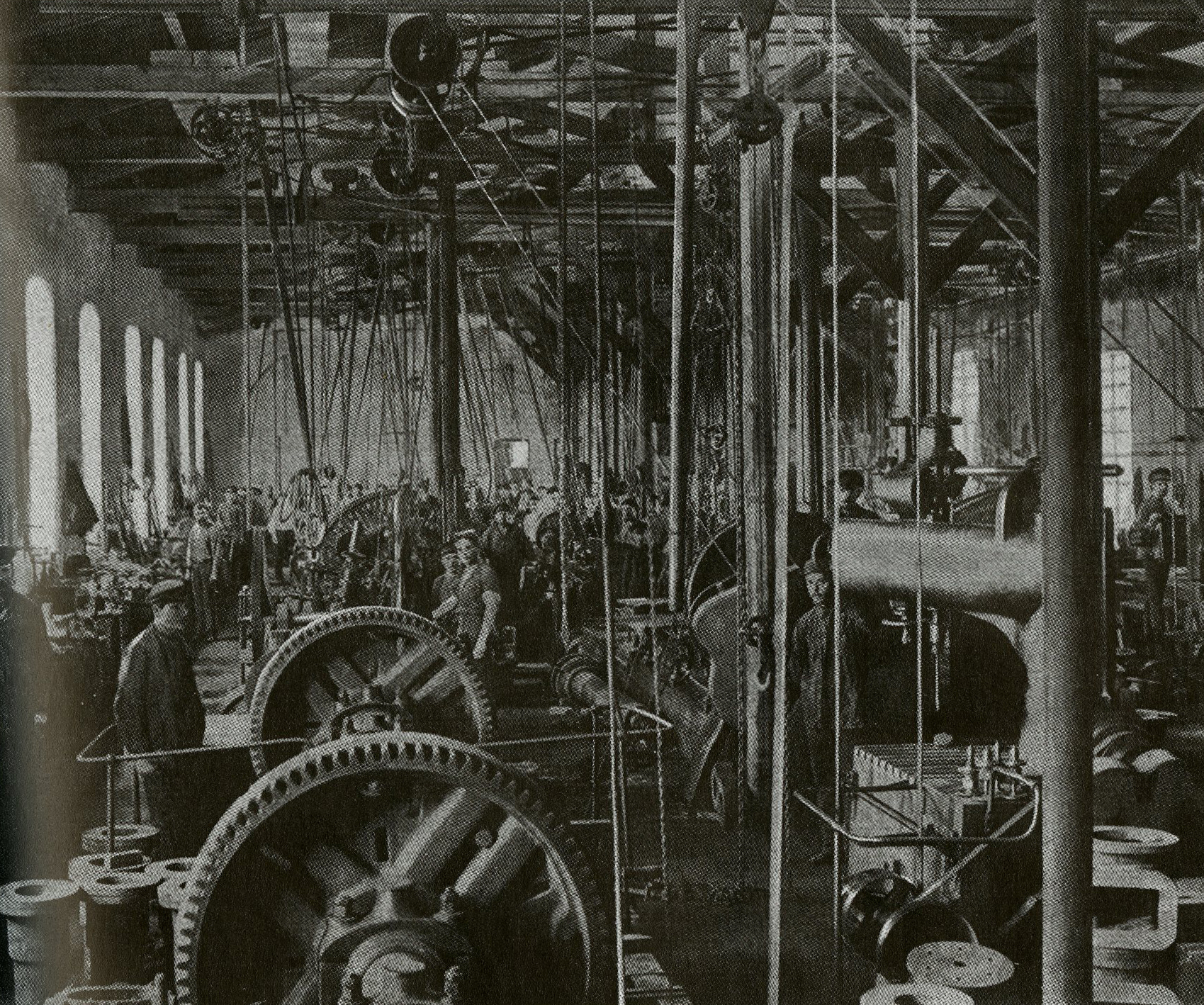

In her early letters home, Ruth increasingly mentions a certain ‘Stickan’. That was the nickname of the Finn Lars Anton Isidor Stigzelius, a shipbuilder from Turku in Finland, who was employed at Nobel’s design office in Tsaritsin in 1880. He went to Baku as a designer in 1887. In 1892, he became head of the engineering department, and he built the vessel slipway in Baku in 1897-98.

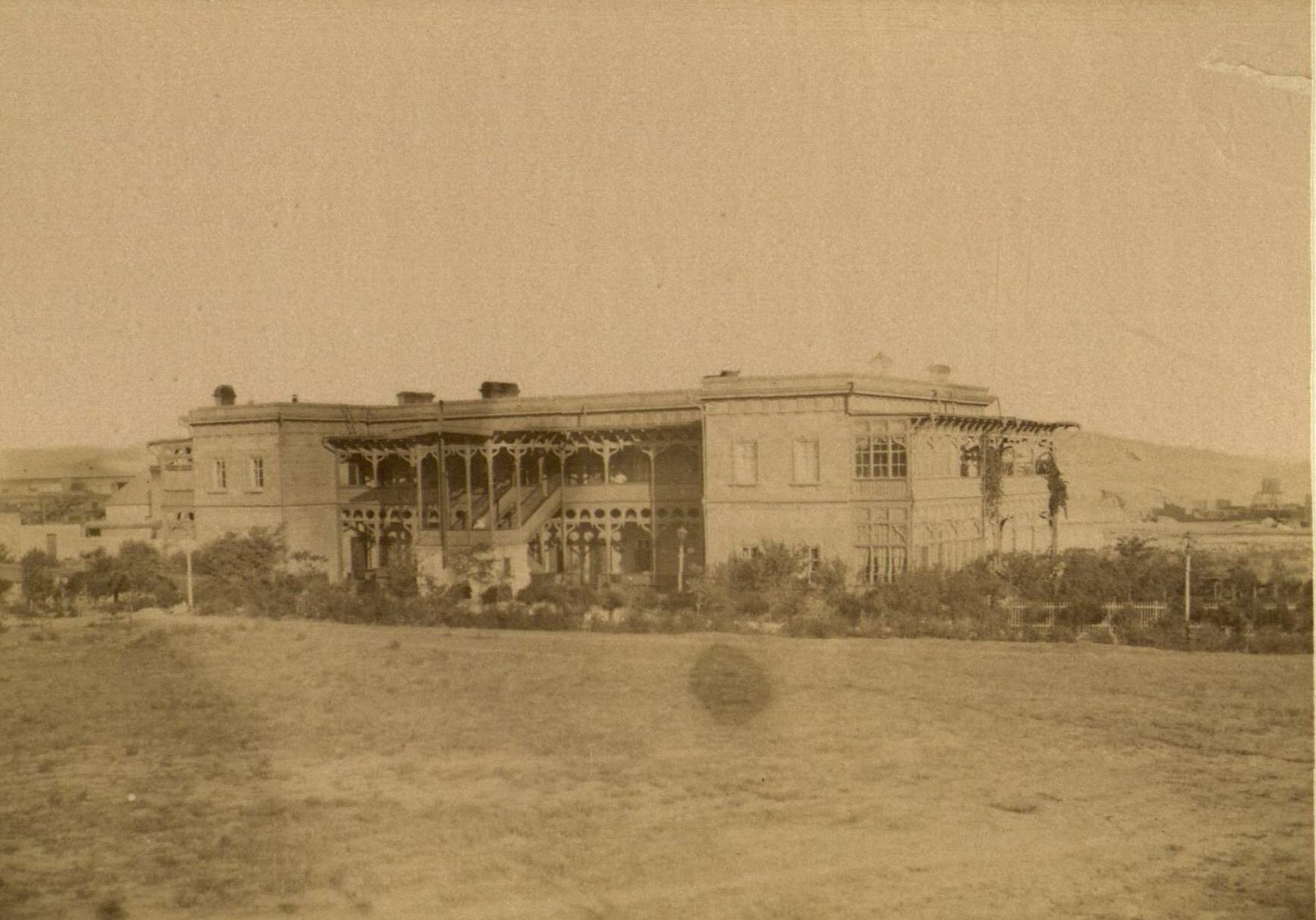

Ruth and Lars married and moved into a staff house in Villa Petrolea. The company had installed a stove in the kitchen that burned oil but did not work property, as Ruth explains in her letters. The stove was rebuilt three times, which made a mess in the kitchen, to the annoyance of the kitchen maid. Over the years, the family had housekeepers, whose quality Ruth commented on in her letters. There were also problems with the electrics, and a telephone was installed. About journalist Ida Bäckman’s report from Baku, Ruth wrote, ‘it was 80 per cent untrue’.

Ruth and Lars had three girls and one son. On 15 April 1903, they celebrated the christening of their first child, Ester. They invited 18 guests. Ruth wrote to her mother Maria that it had exceeded expectations and that Emanuel Nobel had said that he had never had so much fun in Baku. The godparents were Emanuel Nobel and Hilda Hagelin, and Gustaf Eklund and Berta Tauson. Ruth writes, ‘Mr Nobel presented us with a christening font in the shape of a scoop in matt silver, inset with precious stones. It must have cost at least 500 roubles.’

At the start of the twentieth century, there was increasing unrest in the area, and things were not as they had been in Baku. The Scandinavian colony nonetheless tried to carry on as normal, and Ruth took big groups of 14 people on long walks to Tatar villages and fire temples. They continued to hold parties with dancing at the ‘Swedish club’, fancy-dress balls with collections for the needy after the earthquake in Italy 1912, played tennis and went to the Lutheran-evangelical church in Baku on Sundays. One consolation was the park that had been established with soil from Lenkoran in the southern part of the country. Ruth writes, ‘We have such beautiful flowers in the garden: stock, wallflower, hyacinths, crocuses, lilies, tulips, pansies and, not to forget, daisies. We also pick a little asparagus every day, so we have enough for about a meal every other day.’ Later, she describes how they enjoy fruit, ‘most recently blueberries and blue plums. There are lots of melons and the apricot tree gave at least 14 litres.’

At home in Norrby(Sweden), her mother Maria grows increasingly worried as she reads the papers about the murders of Swedes and she writes, ‘you may live among savages and Tatars, but I have great confidence in Lasse; he’ll make sure you are safe.’

Ruth and her family left Baku in 1913 after her husband Lars’s diabetes became worse. Lars Stigzelius died in Stockholm three years later.

(more info)

Newly qualified physiotherapist Ruth Grapengiesser, later Stigzelius.

(more info)

(more info)

(more info)