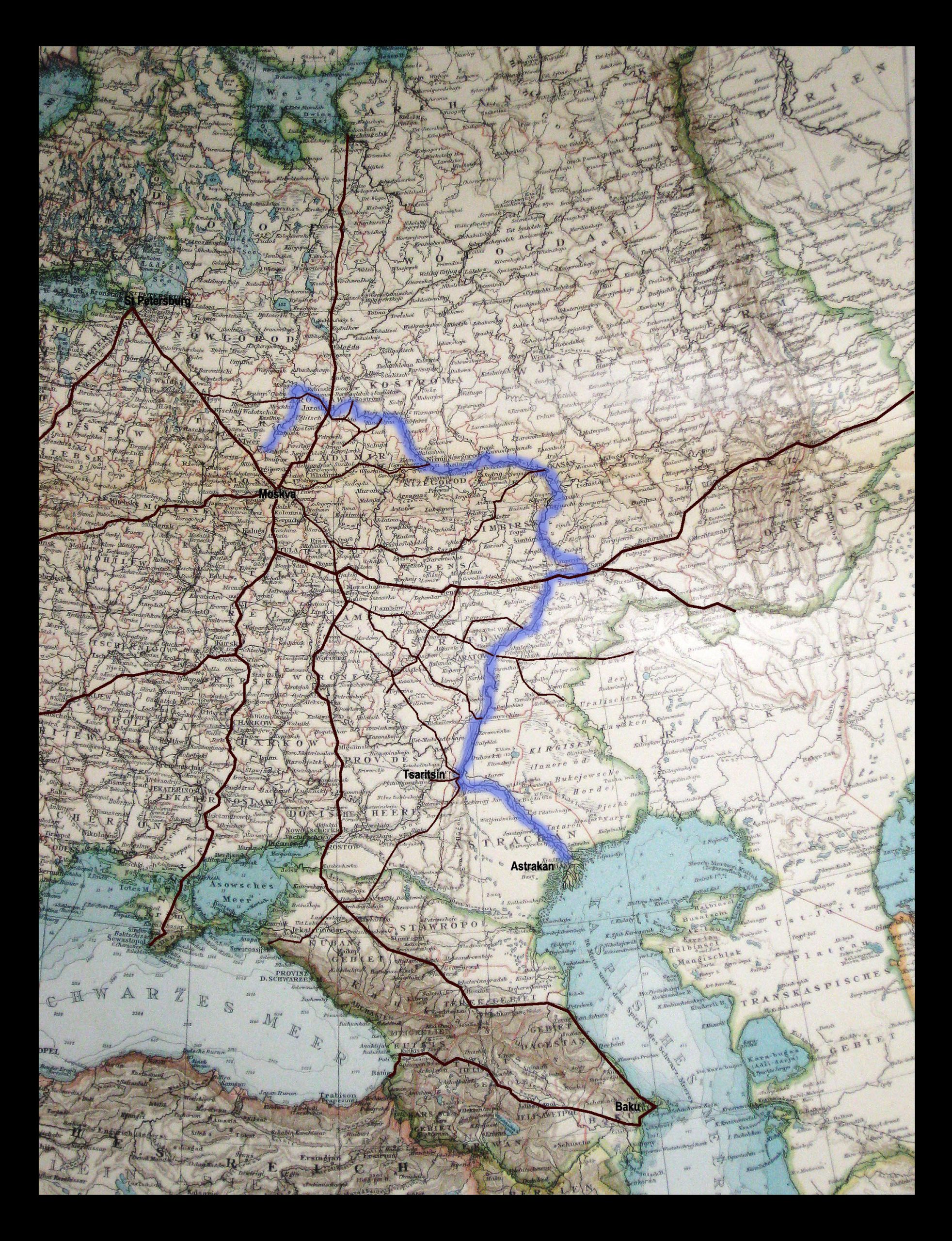

It is one thing to bring oil to the surface, and quite another to transport it to customers. Around 1880, the Branobel company had to create its own transport system from Baku on the southern border of the Russian Empire. The town of Tsaritsyn, later renamed Stalingrad, became an important hub in the distribution network.

In March 1878, Ludvig Nobel wrote to his brother Alfred, stating that “the work at the factory is going extremely well. The major rewards I was able to give out for the past year encourage the spirits and working capacity of my workers.”

There were now 1,200 men working at Branobel. They expected that their earnings ought to be at least double by 1877. Emanuel Nobel reported from Baku to his father Ludvig, president of all the Nobel companies in Russia, by letter once a week, describing the situation “with great clarity and well-chosen words. This allows me to hope that he will become a serious man, and what I had started would not need to fall into decay.” Robert had made a profit of 4,000 roubles, which “will please him and raise his spirits. I myself am now so blasé regarding money that 4,000 more or less has no effect on my mood.”

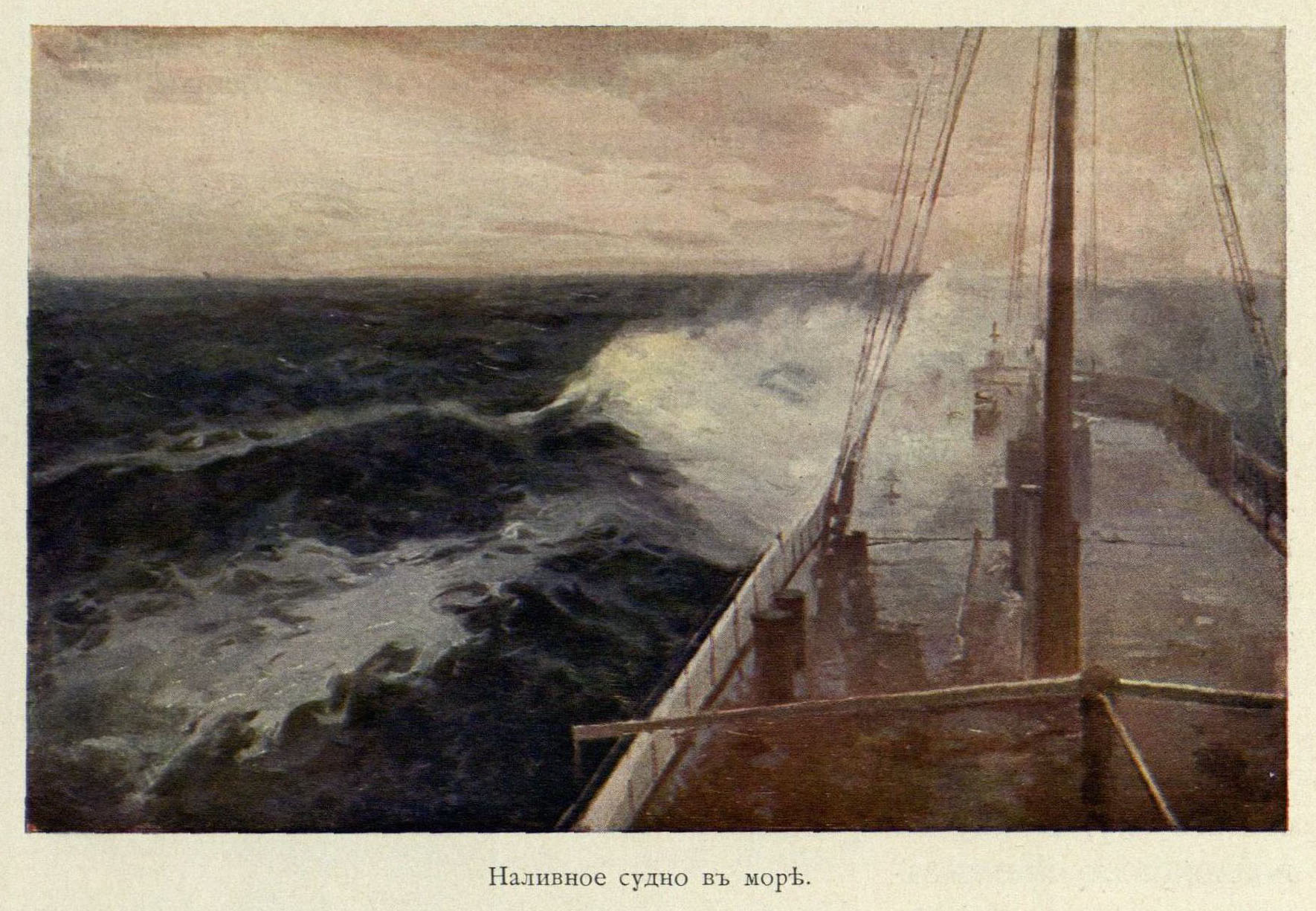

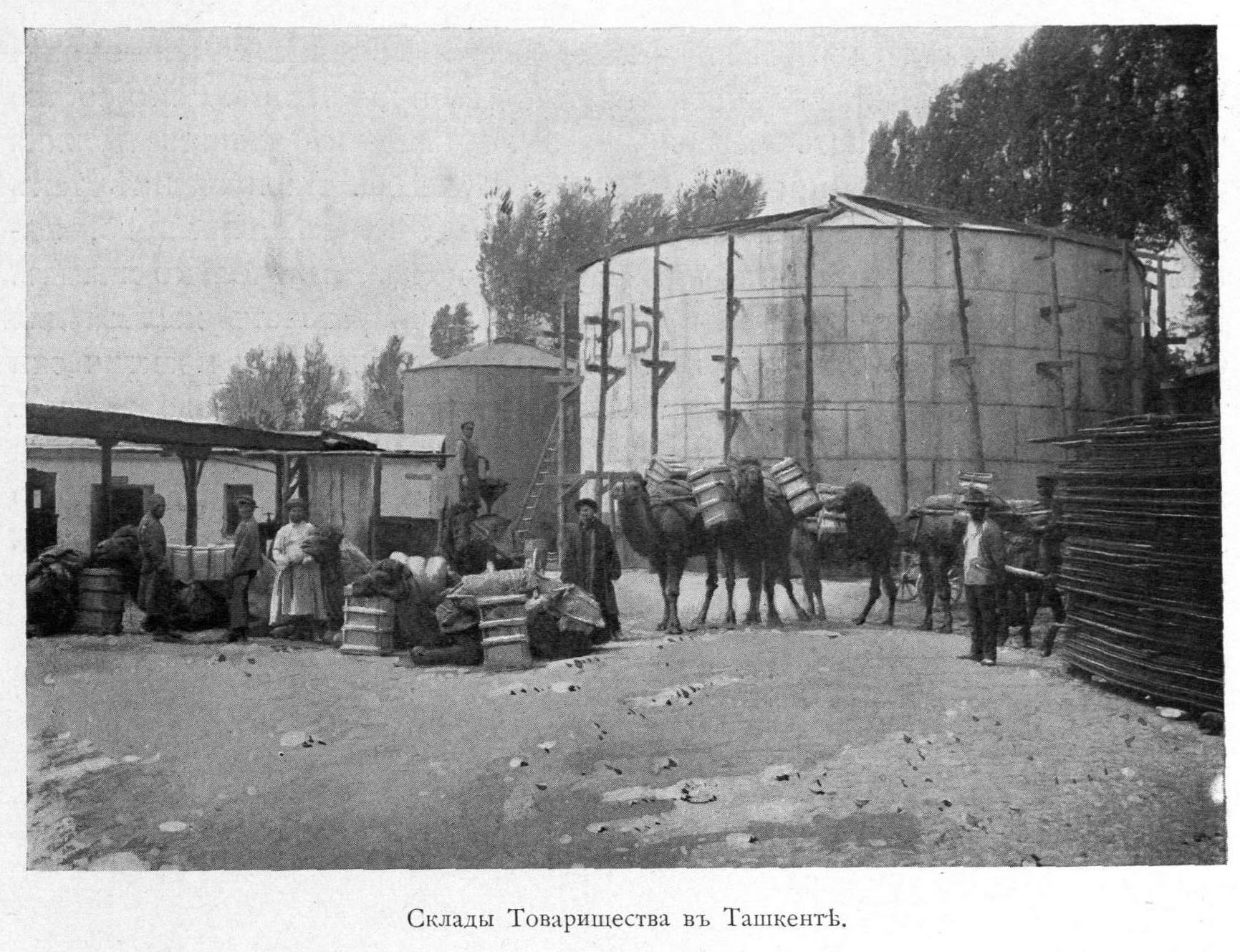

All went well, but one problem was that the weather governed the oil company – from November to the end of February, the River Volga, on which the products were transported north to the Russian and European markets, froze. During the ice-free period of the year, the tanks at the depots along the river had to be filled with petroleum products. From Baku’s loading docks, the tank steamers left for Astrakhan at the mouth of the Volga, where the oil was reloaded on to barges, which were pulled by small tow boats up towards the large tanks at Tsaritsyn. Storage depots were built along the waterways at a great many locations.

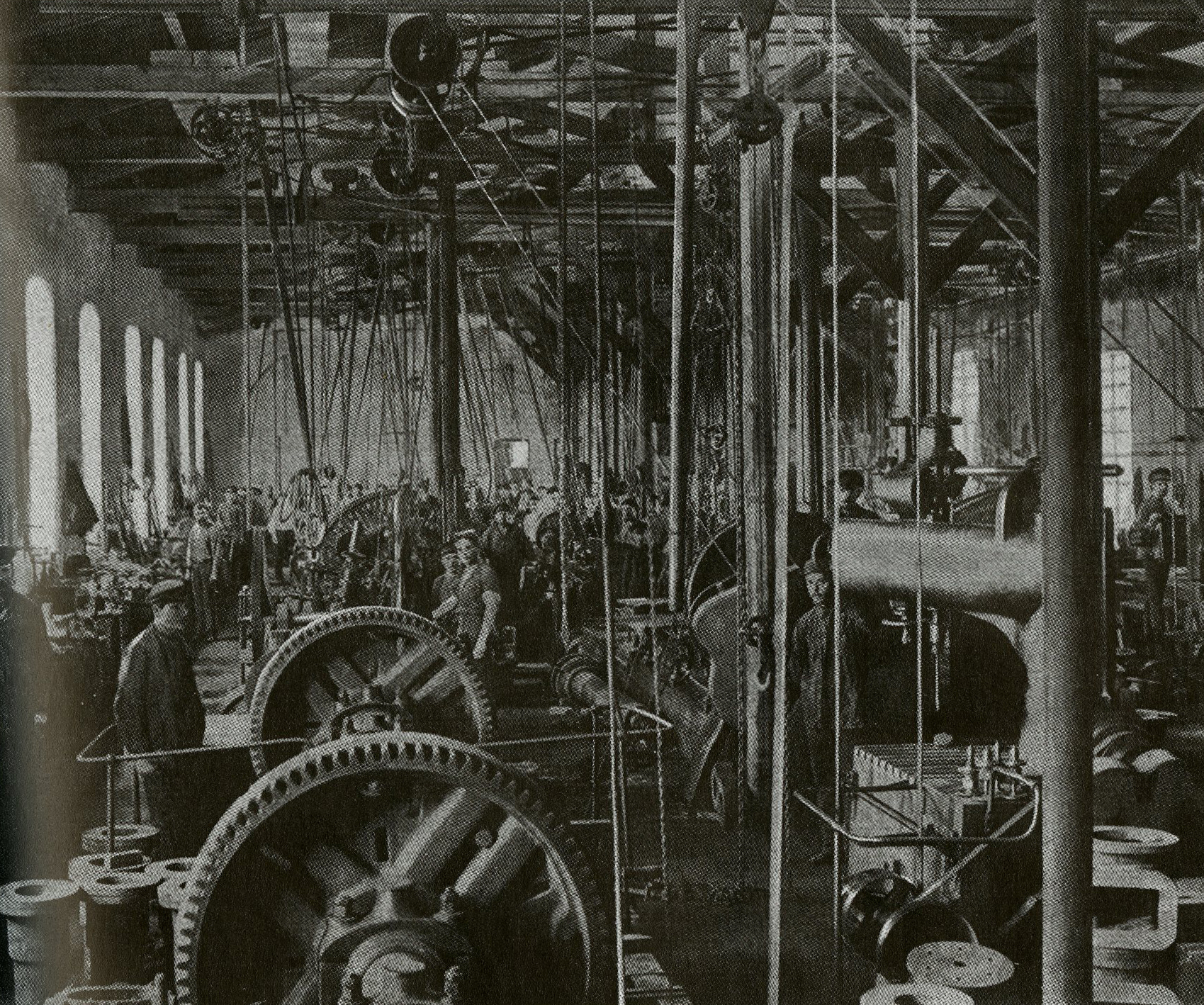

Tsaritsyn became an important hub, with shipyards and mechanical workshops for maintenance and repairs to railway locomotives and tank wagons. But transport in barrels was also necessary. Wood was expensive and difficult to get hold of. Some manufacturers purchased empty barrels from America. In Tsaritsyn, Branobel set up a factory for manufacture of metal barrels on an industrial scale, following specific studies in the USA.

Ludvig wrote about the depot in Tsaritsyn: “Everything bears the mark of order, system and purpose. Our roads are paved, the bridges are in a good state of repair, the buildings roomy and comfortable, neat and tidy, and the technical facilities create an overwhelming impression. The huge tanks together held over 1,250,000 puds (20,000 tons) of paraffin, and the pumps are mighty objects.”

When Ludvig and Robert drew up their plan for the system in 1877, oil companies in the USA had been using tank wagons for ten years. The railway was required to distribute oil products across the vast expanse of Russia. However, the Russian state was completely uninterested in manufacturing tank wagons. So Ludvig, with the help of an engineer from the Riga Wagon Factory, designed tank wagons and locomotives himself that could pull goods trains carrying 250 tons of paraffin. Branobel extended the railway with sidings to the storage depots.

Russian railway personnel sold paraffin to retailers and agents in the area at station stops. However, the product could not be touched until the payment had reached the office in St. Petersburg. The head office in St. Petersburg was kept informed of the current location of the tank wagons by telegraph. The positions were marked on a huge map using pins. The railway stretched throughout Russia, all the way to Vladivostok.

(more info)

(more info)

(more info)

(more info)

(more info)