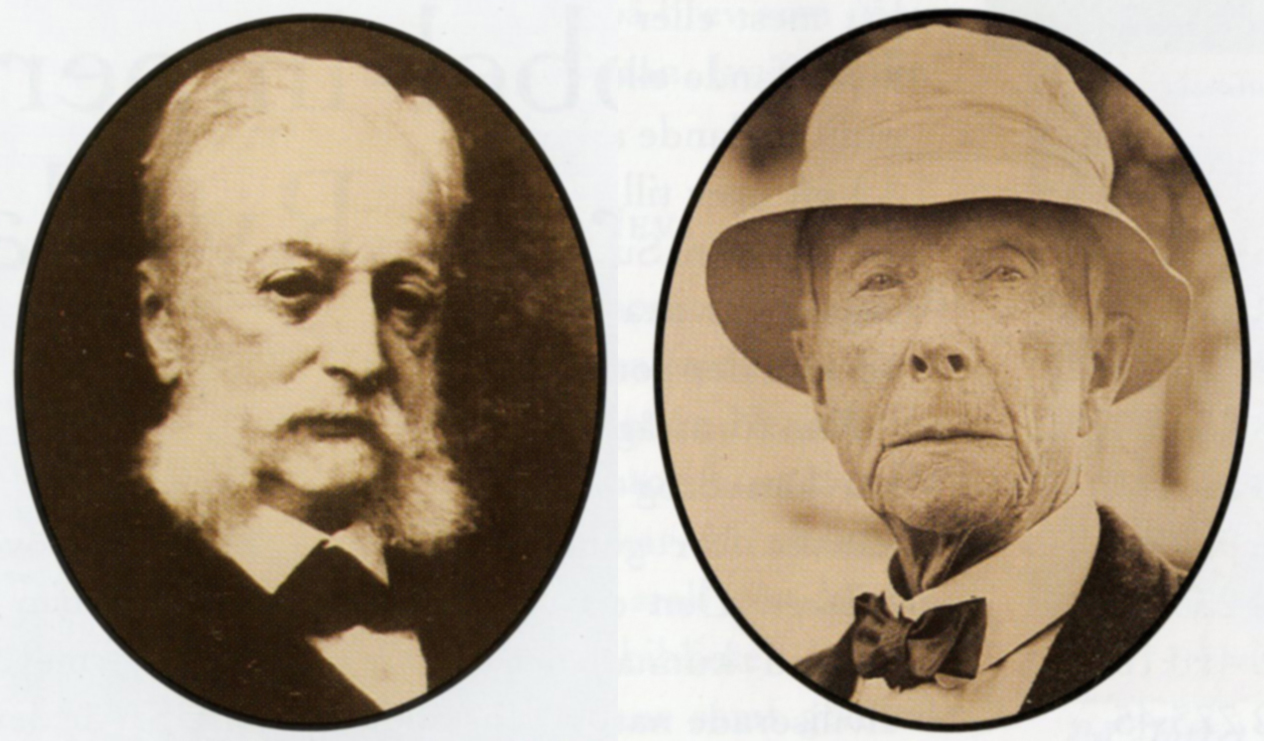

The development of the Caucasus Oil industry directly affects Rockefellers’ “Standard Oil”’s European monopoly. In order to better compete with the latter Ludwig reinforces “Branobel”’s positions in the Black Sea and initiates the building of the longest pipeline through Georgia.

In the 1870s Russian industrialists Bunge and Palashkovsky began constructing the Baku-Astrakhan-Volga railway. Since the project was financially highly burdensome and the work was going quite slowly, Bunge and Palashkovsky contacted the French branch of the Rotschild family. The latter being involved in railway business for decades (constructions of first railways in Europe were related to Rotschilds’ names) not surprisingly responded positively. Sensing what could have brought these new sources of kerosene and oil it was in Rotschilds’ immediate interest to connect Baku to Batumi and use the latter for extensive export.

The Nobels too agreed to the idea. Thus Ludwig was writing from Baku to his brothers Alfred and Robert in Petersburg: “From all the routes available for oil transportation from Baku I recommend, to choose the one through Georgia, because of friendship and mutual loyalty existing between Georgians and Azeris for centuries. For us, foreigners, this factor is of considerable importance. Since all other routes involve much more danger, and because there are no such favorable conditions elsewhere except for both Baku and Tbilisi, I’m sure that we should choose exactly this route.”

Finally, Ludwig triumphed. It was agreed to export hydrocarbons to Europe according to his plan – by Baku-Tbilisi-Batumi railway for the completion of which the necessary 10 million U.S. dollars were provided by Rothschilds. They also distributed small credits for the creation of oil refineries in Batumi.

Nobels were well aware they would not be able to cope with Europe’s biggest financial power. Rotschilds’ interests were primarily in banking and investments, and less so in overall management. With Nobels being against such speculations, the clash of two business ideologies was inevitable. The situation came to a head in 1881, when after the assassination of the Russian emperor Alexander II, an imperial decree was issued prohibiting the Jews from buying or renting any land in Russia. However, the law did not hinder the Rotschilds from carrying on with their plans and in 1883 the Baku-Tbilisi railway was completed. Rotschilds also established Societé Commerciale et Industrielle de Naphte Caspienne et de la Mer Noire, more known by its Russian abbreviation – БНИТО (BNITO) for more effective competition with Nobels.

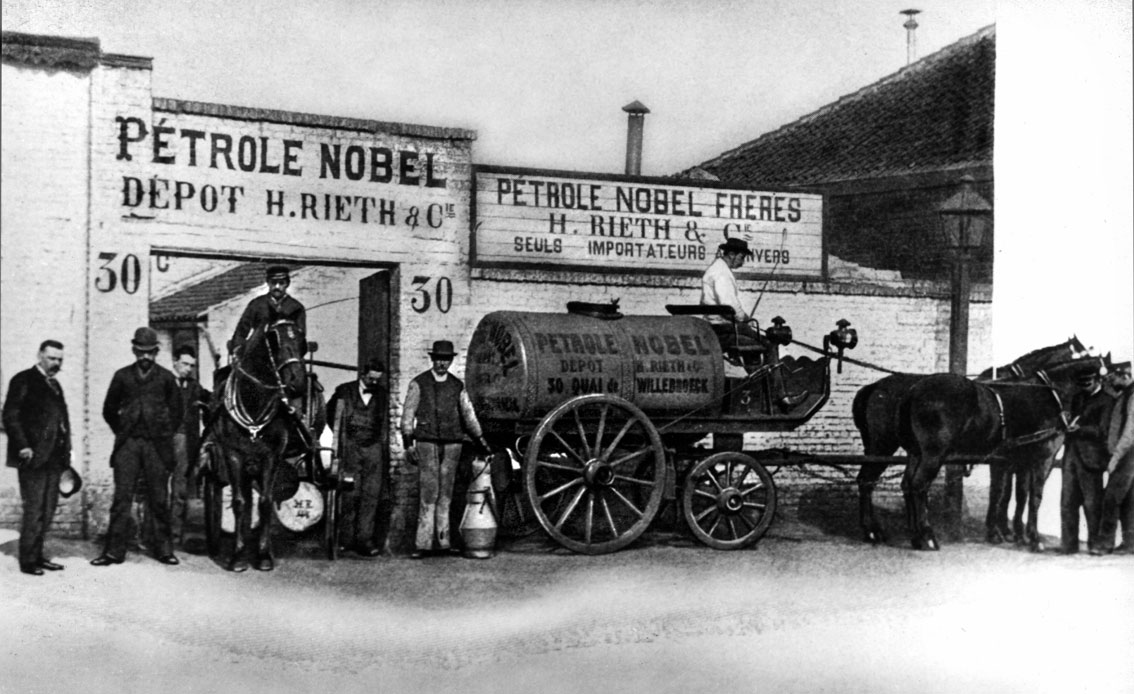

With “BNITO”’s successes and its establishment as a number two on the Russian oil market, Batumi was transformed into a veritable business centre. British ships converted into tankers transported kerosene and oil to Fiume and Marseille. Rotschilds also owned the biggest factory in Batumi producing cases for oil and kerosene transportation. Their business activities were partly hindered by the imperial revocation of Batumi’s “porto franco” status in 1886. The city once again had become a military port.

Nobels avoided engaging into a life-or-death war with Rotschilds. Alfred (living at the time in Paris) was well aware that his brothers could end up on a loser’s side. By his initiative and support a conference was convened in May 1884, in Paris, where two families agreed to cooperate on vital business issues. It was in Rotschilds’ direct interests to ship kerosene into Europe which for decades was a monopoly of Rockfellers’ “Standard Oil”. It coincided with Nobels’ interests too. Therefore, their support for the enterprise was guaranteed. Ludwig also proposed to sell a part of the Branobel company shares to Rotschilds in order to buy with the received money “Batumi’s Oil” and “Trade Company” from the Russian oil industrialists Bunge and Palashkovsky for 1,5 million rubles. Ludwig also intended to build a new factory for the production of oil and kerosene transportation cases and a pipeline through the Surami Pass.

Although the Nobels were quite confident in the success of the proposition, Rotschilds refused. The ever ubiquitous Rockfellers sensing disagreements between their two main rivals entered the scene with the goal to further widen the gap existing between them by negotiating on the one hand with the Nobels and maintaining close contacts with the Rotschilds on the other.

To effectively protect his company Ludwig signed new contracts and reinforced his positions in the Black Sea trade by bringing in a 286-feet-long tanker “Свет” (The Light) meant to ship 17000 tons of kerosene to England. It was a huge blow to the Rockfellers’ “Standard Oil”’s positions. The company, which controlled America’s 90% of oil and kerosene export considered England’s market as its monopoly. Nobels’ product eventually took on 30% of England’s oil market. The progress was stunning considering the fact that several years before the percentage was only 4%.

It was also quite apparent for the Nobels that in order to successfully compete with such giant oil companies it was absolutely important to increase oil production output. Initially additional transport cars were used and several new refineries were built in Batumi, but it still could not provide the necessary output level. That is how the idea of constructing a pipeline came to a limelight.

The Surami Pass constituted the main hindrance for the pipeline. In 1883 Ludwig, during the works on Baku-Tbilisi railway, proposed to the local authorities to build a pipeline. The authorities refused him the concession. The reason: the tsarist government feared the increased oil output and effective competition with the Rockfellers would make the Nobels to put a higher price on still very cheap Baku oil. Ludwig founded in Baku the first syndicate and demanded transporting the oil through the four-kilometer-wide Surami Pass. The Russian chemist Mendeleev too was an ardent proponent of the project. Eventually, the construction began but was only completed by 1903, constituting 835-kilometer-long pipeline with 19 pumping stations. The construction was largely done by handwork. Pipelines were connected with threaded clutches and anticorrosive isolation was used for better protection. Along the main pipeline a telephone connection was also established. Across the river Kura the pipeline was suspended on one of the railways’ bridges. Having the overall capacity of up to 900 000 tons of hydrocarbons per year the construction of the pipeline consumed 400 tons of Alfred’s dynamite with the overall cost of the project reaching 12 million rubles.

Nobels built a large oil terminal in Batumi. Some of the tanks created by them are still visible today after nearly 120 years. With many residential houses built by them for the managerial staff, the main building served also as a headquarters of the consulate of the United Kingdom of Sweden and Norway in the Caucasus. One document dated to June 5 1897, held in the National Archives of Georgia, attests to the approval by the local authorities of Gustav August Hager’s appointment as a vice-consul of Sweden-Norway.

Situated on Leselidze Street in Batumi, the consulate was transformed in 2007 into the Nobel Brothers Batumi Technological Museum. Another interesting historical document is about the resolution of Nobel Oil Society to open a third-grade private school in the Black Town (Baku) from 1886, as well as about the establishment of five scholarships in the name of Ludwig Nobel at the Baku Real School from 1890 onwards. Nobels continued their activities and were constantly on business trips to Georgia till the end of the Tsarist rule in 1917.

(more info)

The idea of a pipeline for transporting oil would replace the older transport way of using trains, and increase the oil output manifold.

(more info)

(more info)