For two years the Russia expert and author Bengt Jangfeldt has been immersing himself in the life and concerns of the Nobel family in Russia during Tsarist times. Now the result has been set out in a new book. Here the author gives a taste of the enthralling contents for readers of Industrial History.

The name Nobel is associated both in Sweden and abroad largely with Alfred Nobel. This is of course in view of the prize he instituted. Many people know that he was an outstanding chemist and an astute businessman. But very few know that the discovery of nitro-glycerine as an explosive substance, later developed into dynamite, was made in collaboration with his genius of a father, Immanuel. Not only Alfred followed in his footsteps but also his brothers Ludvig and Robert, who unlike Alfred made their careers in Russia.

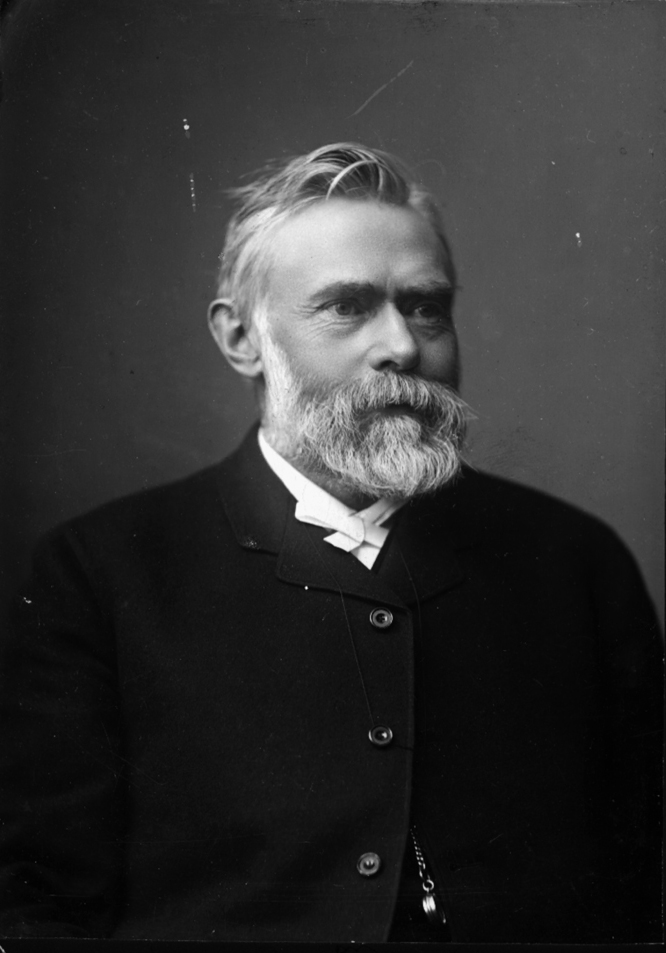

UNIVERSAL GENIUS

Immanuel Nobel (1801-1872) was a universal genius: architect, inventor, engineer, designer. He built Sweden’s first pontoon bridge, he designed private villas, founded Sweden’s first rubber factory and made inventions for the armed services, including water-tight soldiers’ knapsacks. All this with only a few years’ schooling behind him. Immanuel was an inventor of genius but a poor businessman. In 1837 he left Sweden to avoid being sent to a debtors’ prison after a bankruptcy. His family – his wife Andriette, his sons Robert, Ludvig and Alfred and his daughter Henrietta – remained behind in Stockholm.

After a year in Åbo (Turku) Immanuel settled in St. Petersburg, Russia’s capital. The Russian government, unlike the Swedish one, showed great interest in his knapsacks, which, when filled with air, functioned as pontoons for a bridge over which a whole battalion could march. Immanuel had also developed an underwater mine, which unlike previous models was ignited by touch and not by a galvanic cable. The Russian government bought the patent for his mines for a sum of money equivalent to several million kronor in today’s values.

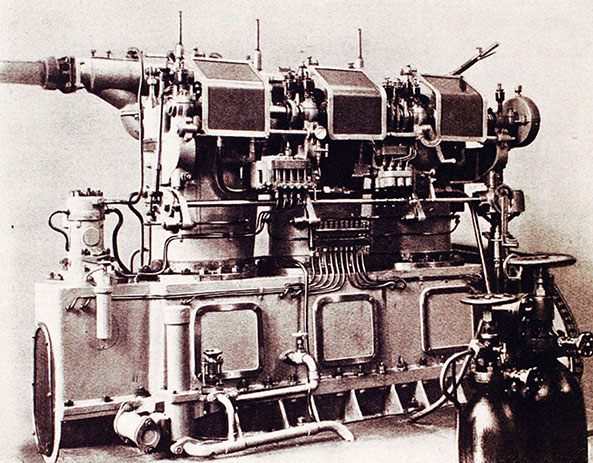

The sale made it possible for Immanuel to send for his family and to start up a mechanical workshop. Robert (born 1829), Ludvig (born 1831) and Alfred (born 1833), like their father, lacked formal schooling and were educated at home. At a young age they were put to work with their father and they were to become good engineers and businessmen. During the Crimean War of 1853-55 the workshop received large-scale orders for both mines and steam engines for the Russian navy and the family became rich. But when the war was over the state reneged on contractual orders and the workshop was forced into liquidation. In 1859 Immanuel and his wife returned to Sweden. The three sons stayed on, charged with trying to save what could be saved of their business.

MANUFACTURER AND REFORMER

The main responsibility for saving the workshop was handed to Ludvig. Thanks to the good reputation of the Nobel name both in professional circles and in certain government circles the bankruptcy was not too severe and Ludvig was able to rent a small machine workshop which, among other things, manufactured water-pipes, heating elements, wheels and waggon axles.

During the 1860s the machine factory was expanded and, thanks to orders from the Russian government, it developed into a successful enterprise. A quarter of a million muzzle-loading rifles were to be converted into breech-loaders, and a large order was placed with Ludvig’s workshop. The commission for manufacturing new breech-loaders also went to him and to his Russian business partner Bilderling. It was an extensive and profitable commission and Ludvig was enabled to buy the workshop he rented. Over the years it developed into one of Russia’s biggest machine factories.

Ludvig was not only an inventor and manufacturer but also someone with a strong commitment to industrial and social issues. He was also fluent in Russian. A problem for the budding but backward Russian industrial sector was the lack of an indigenous workforce. A large part of the population were serfs and illiterate. Qualified workers were fetched from Sweden and Swedish-speaking Finland. To remedy the problem, according to Ludvig, the factory owners ought to be forced to offer their workers an elementary school education. Another problem was drunkenness, which he managed to overcome in his own business by paying out wages more often than was usual. For the more senior office-workers and engineers a profit-sharing scheme was introduced, which meant that 40% of the business’s profits accrued to the scheme. These measures were revolutionary and brought Ludvig a deserved reputation as an industrial reformer.

GRIPPED BY OIL FEVER

Ludvig remained in Russia for the rest of his life. Alfred, who studied to be a chemist, returned to Sweden in 1863 and soon moved abroad to build up his dynamite empire. Robert was just as talented as the other brothers but was endowed with an unmanageable temperament that often upset his business plans. After several years as head of the Nitroglycerine Company Ltd. in Stockholm he returned in 1870 to St. Petersburg to help Ludvig with his work there. The collaboration went well, but Robert really wanted to have an independent position and Ludvig gave him the task of delivering walnut trees for rifle butts which were manufactured in his weapons factory. But when in 1873 Robert came to the Caucasus, where the walnut woods grew, he was gripped instead by oil fever. The area around Baku was abundantly rich in oil and the Russian state had just relinquished its land monopoly and auctioned off oil parcels. Robert was too late to buy oil-bearing land but managed, with Ludvig’s help, to buy a little paraffin factory. With this, the foundation was laid for one of Russia’s biggest industrial success stories: “the Nobel Brothers’ Oil Company Ltd.”, or “Branobel”, as it was usually called.

The background to his success can be sought in Robert’s genius for business. He immediately identified the logistical problem of the business, namely transport of the oil. This was freighted by mules in barrels from the oilfields to the refineries in Baku. Then it was taken on by sailing ships via the Caspian Sea and the Volga to the consumers in Russia. This was both uneconomic and a fire risk. With the help of Ludvig’s money Branobel built pipelines from the fields to the refineries and to the harbour from which the oil was freighted further in oil tankers, not in sailing vessels. The world’s first tanker, Zoroaster, was built by Nobel Brothers in 1878. These innovations within the transport industry gave “Branobel” a lead over their rivals which the latter were never able to recover from.

In 1880, for health reasons, Robert left Baku and returned to Sweden, where he died in 1896, the same year as Alfred. Ludvig died in 1888. The family, who were sole owners of the machine factory and had the majority of shares in the oil company, were by that point very rich.

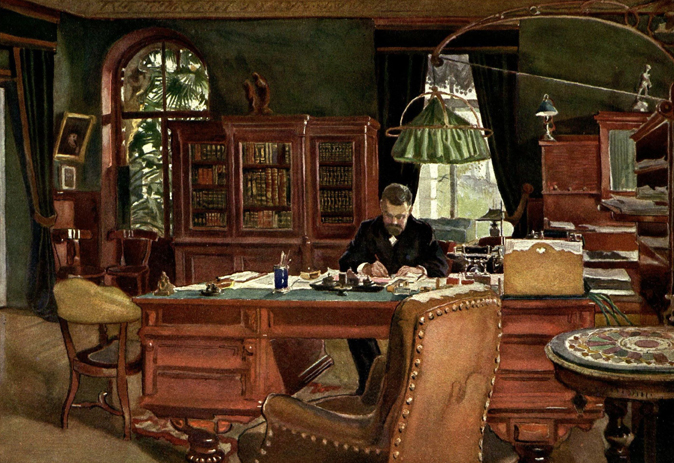

After Ludvig’s death the business was taken over by his sons Emanuel and Carl. The latter died as early as 1893 and thereafter the family businesses were run by Emanuel. He lacked his father’s inventive genius but was an exceedingly capable businessman. Under his leadership the Nobel industrial empire grew into one of the most powerful in Russia. Emanuel, like his father, was a reformer in the social sphere. Houses and schools for the employees were built beside the machine factory in St. Petersburg and by the oilfields in the Caucasus, as well as schools for their children. During the First World War the business premises were converted to Red Cross hospitals.

THE END OF RUSSIAN SAGA

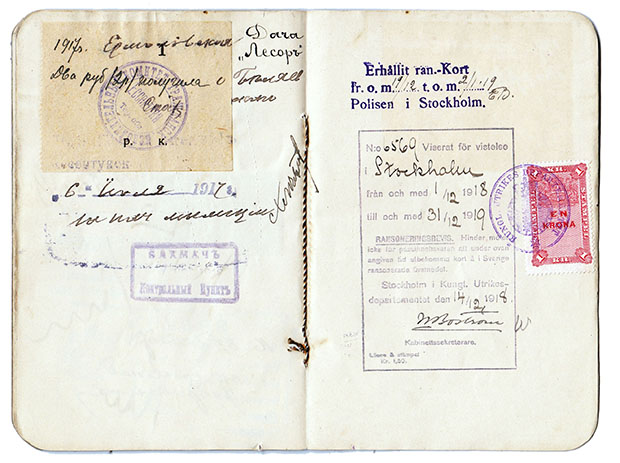

The Nobel empire disappeared in the revolutionary storms of 1917 that swept away all private enterprise. The Nobel family were forced to leave Russia, where they had been active since 1838. In the Soviet Union the Nobel name was plunged into total oblivion, but since the fall of Communism it has been fundamentally re-appraised. If during the Soviet era the Nobels were accused of being exploiters they are now seen as model capitalists. In 1991 a monument to Alfred was erected in St. Petersburg and the contributions of Ludvig, Robert and Emanuel are now hailed as emphatically as they were formerly condemned. In Baku the motorway that runs through the city has been christened Nobelprospekt.

First pariah, then hero … a leitmotif in Russia’s history. Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Andrei Sakharov, Joseph Brodsky – all expelled in Soviet times, now statues in Russian cities. The Nobel family belong to the same elite company, whose “dissidence” was not literary nor political but consisted in the fact that they were entrepreneurs of genius and successful businessmen.

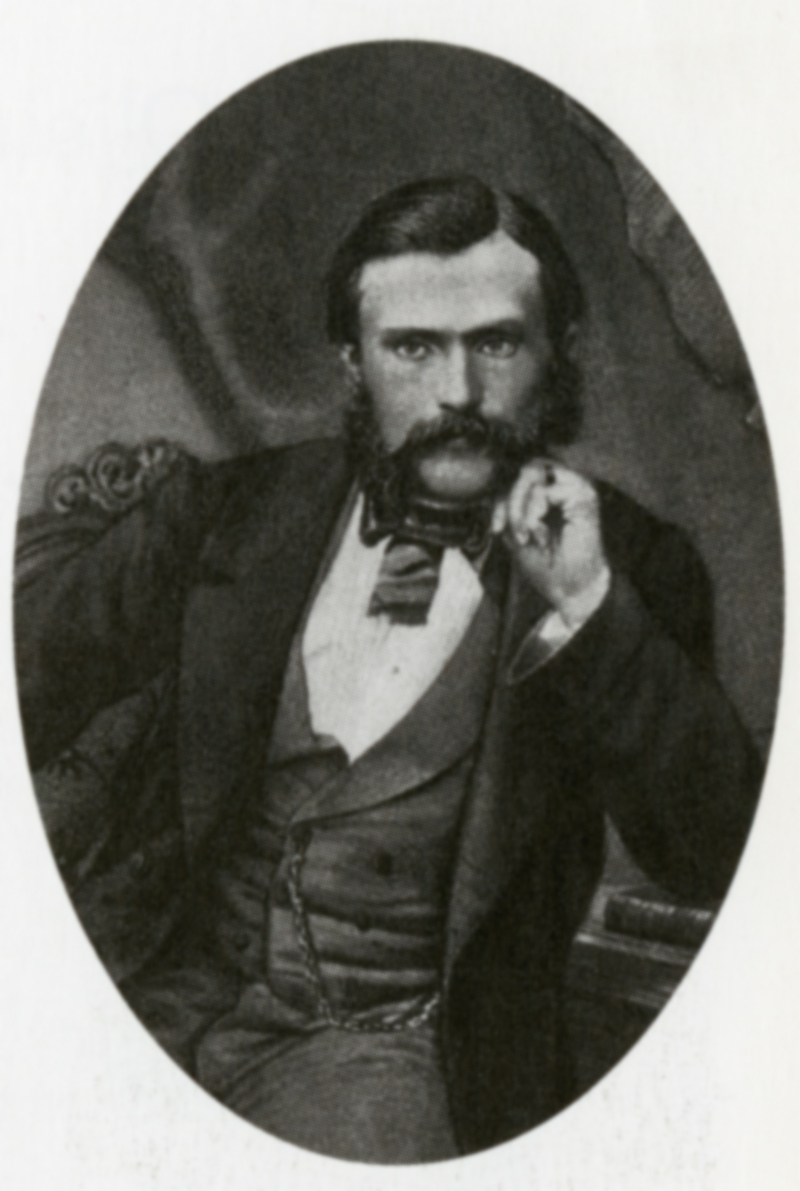

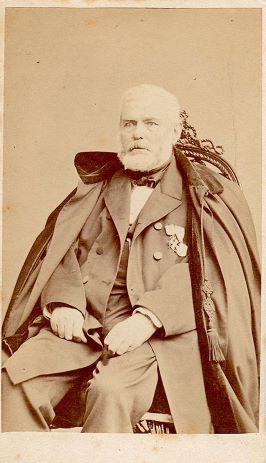

The last known photo of Immanuel Nobel.

(more info)

(more info)

(more info)

(more info)