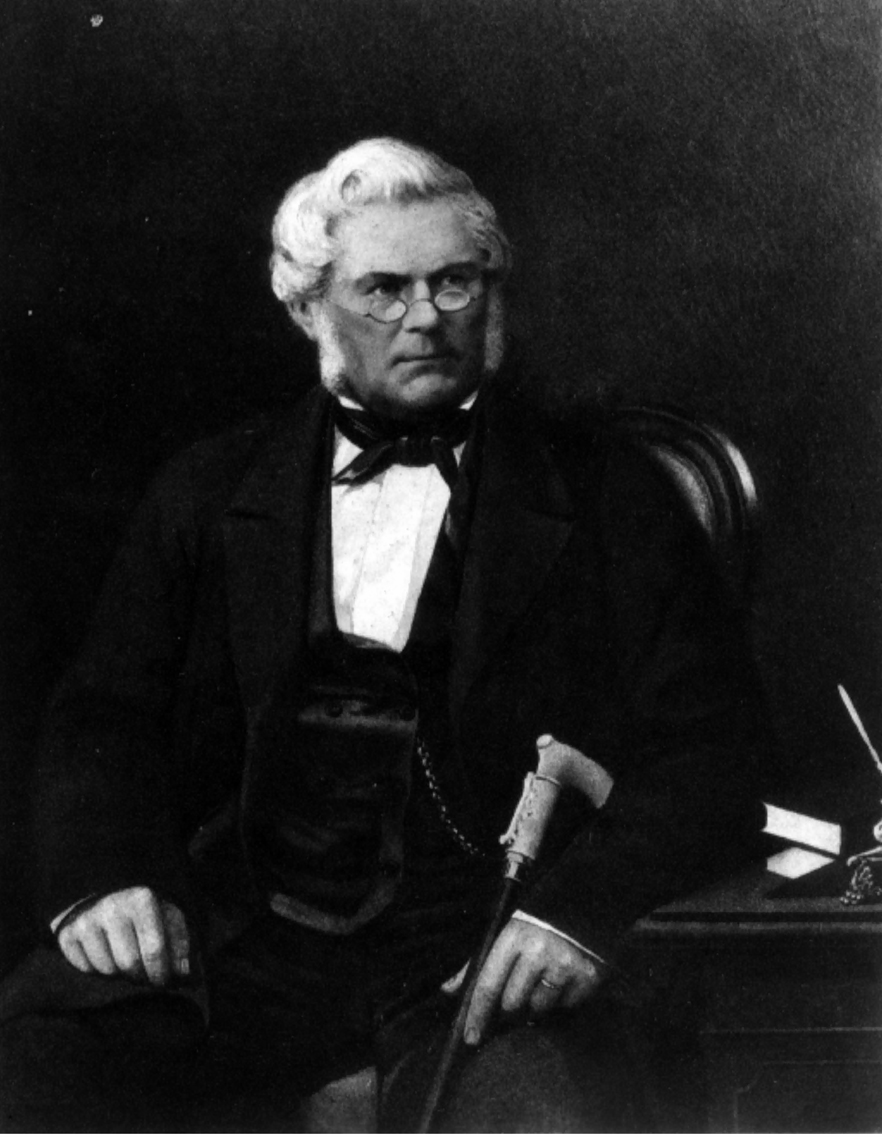

The father of the Nobel brothers, Immanuel, was an important inventor whose work interested him more than financial gain. When he was on the edge of bankruptcy, he sought a new future in St Petersburg where his fortunes were reversed. Among other things, he received the Tsar’s imperial gold medal before he once again ended up in financial difficulties and was forced to return to Sweden in 1859.

The Nobel family can be traced back to the 17th century through Petrus Olai Nobelius, who originated from a peasant family in Östra Nöbbelöv in Skåne, Sweden’s most southerly province. Petrus married Wendela, the daughter of the universal genius and rector of Uppsala University, Olof Rudbeck. Their son Olof Nobelius in 1746 married Anna Christina Wallin (Nobelius) who bore him 7 children of which only 5 survived to adulthood. Their youngest son, born 1757, was christened by the name Immanuel (senior).

Immanuel Nobel senior served as a field cutter and as a military surgeon. He became a widowman in 1795 and five years later remarried with Brita Katarina Ahlberg. Their first-born son (24 March 1801) got the same name as his father, Immanuel (junior).

Immanuel’s early schooling was poor, but he later took part in lessons at the Royal Swedish Academy of Agriculture’s engineering college in Stockholm, probably between 1822 and 1825. During his period of study, he received awards and scholarships for his designs. In March 1828, at the age of 27, he applied for patents for three inventions, a planer, a mangling machine and a mechanical movement. He was engaged more and more as a building contractor and engineer. In 1827 he married Andriette Ahlsell, whose family consisted of public officials and civil servants in Stockholm. They had eight children, with Robert, Ludvig, Alfred and Emil surviving infancy.

Immanuel worked hard but encountered serious mishaps and became bankrupt in 1833. Four years later, his creditors threatened him with debtor’s prison, but, at long last, Immanuel became free from debt. He moved over to chemical experiments and, in 1837, decided to seek his future in Finland. From there, he continued after a while to St Petersburg where his luck turned and his family, who had remained in Stockholm in meagre circumstances, were able to join up with him in 1842.

His machine for manufacturing wheelhubs was renowned, just as his designs for mines to ”destroy the enemy at considerable distances” attracted attention in the Russian armed forces. It was not until the outbreak of the Crimean War in 1854, however, that he received any orders from there. At that time, his eldest son, Robert, was also working on mines in accordance with Immanuel’s instructions. This contributed to a great extent to the successful Russian defence of the naval base in Kronstadt against attack from the English navy.

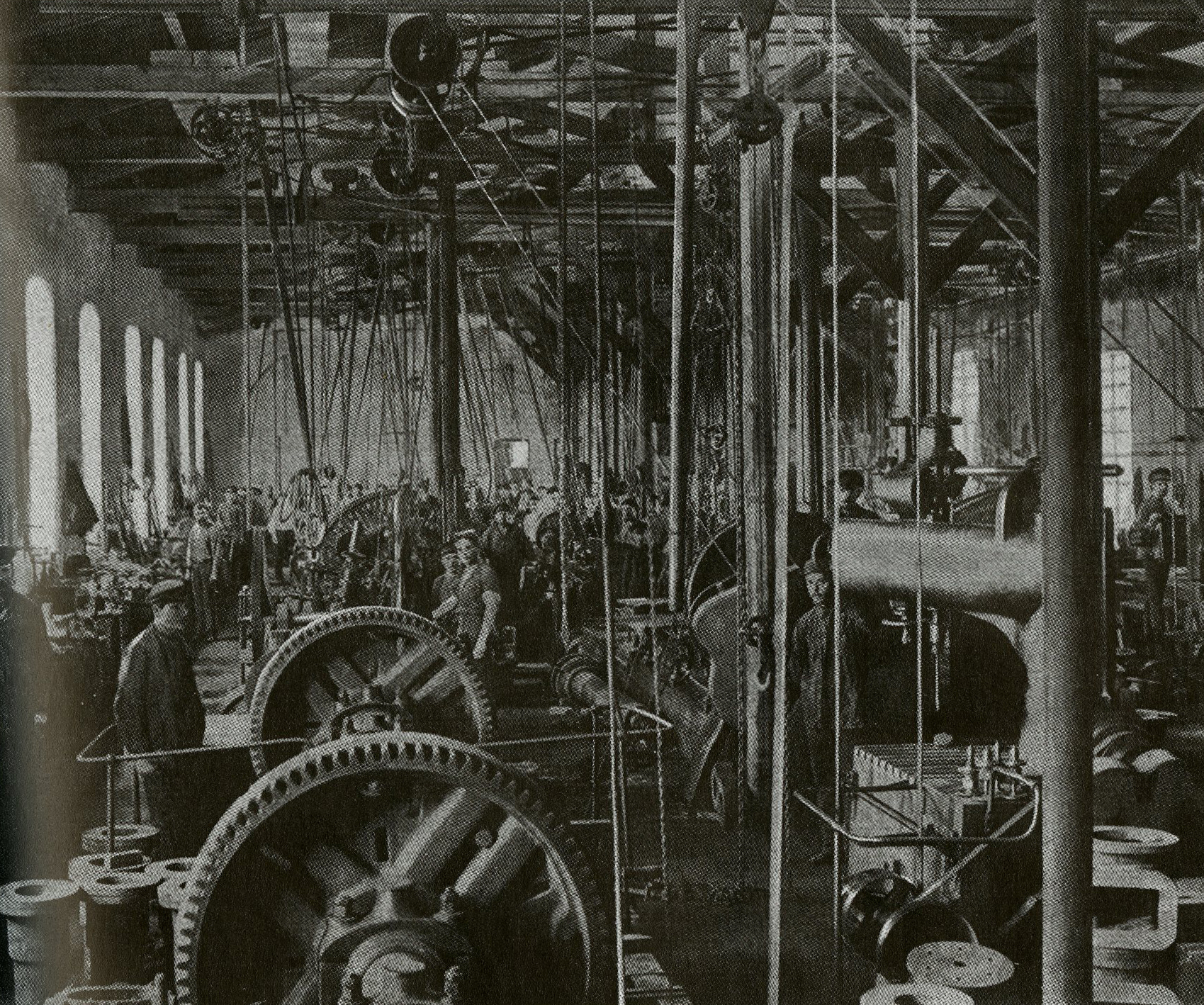

Immanuel was now earning a lot of money and opened a mechanical workshop with a foundry, where he manufactured wooden carriage wheels and systems for heating warm water for housing. Despite severe difficulties, he also made 11 steam engines for warships, which brought him an imperial gold medal in 1853. After being promised several order, he greatly increased his activity. But, when Tsar Nicholas I died in 1855, the Russian government concluded peace and returned to ordering from abroad. Once again, Immanuel was on the edge of bankruptcy. He left his factory to his creditors and moved with Andriette and their youngest son, Emil, back to Stockholm in 1859, where they rented the house, Helenelund, in Södermalm.

In 1863 their son, Alfred, also returned to Sweden to begin experimenting with a mixture of gunpowder and nitroglycerin together with his father. With the patent in their pocket, they began working in their own workshop in Helenelund, north of Stockholm. The younger son, Emil, who had just passed his higher school examination in Uppsala, was working in the workshop when it exploded on 3 September 1864 and Emil was killed. Some months later, Immanuel had a stroke and was confined to bed. There, he contemplated the spirit of the times and wrote the paper ”Försök till anskaffande af arbetsförtjenst till förekommande af den nu, genom brist deraf tvungna utvandringsfebern [Attempt to obtain earnings to accommodate the emigration fever resulting from the lack of this]”, which was published in 1870.

Immanuel was an important inventor whose work interested him more than financial gain. With a ten percent dividend on 25 shares in his son Alfred’s Nitroglycerin AB, the wolf was kept from the door. In his estate in 1872, a residue of SEK 28,700 was entered. His wife, Andriette still had the shares when she died 17 years later. By that time they were worth eight times more than when she and Immanuel got them.

Immanuel Nobel was always more interested in the inventions than the financial gains, forcing him into several bankruptcies.

(more info)

A watercolour painted by Imanuel Nobel himself in which Imanuel, on the left of the hill in the foreground, demonstrates his underwater mines to Tsar Nicholas I.

(more info)