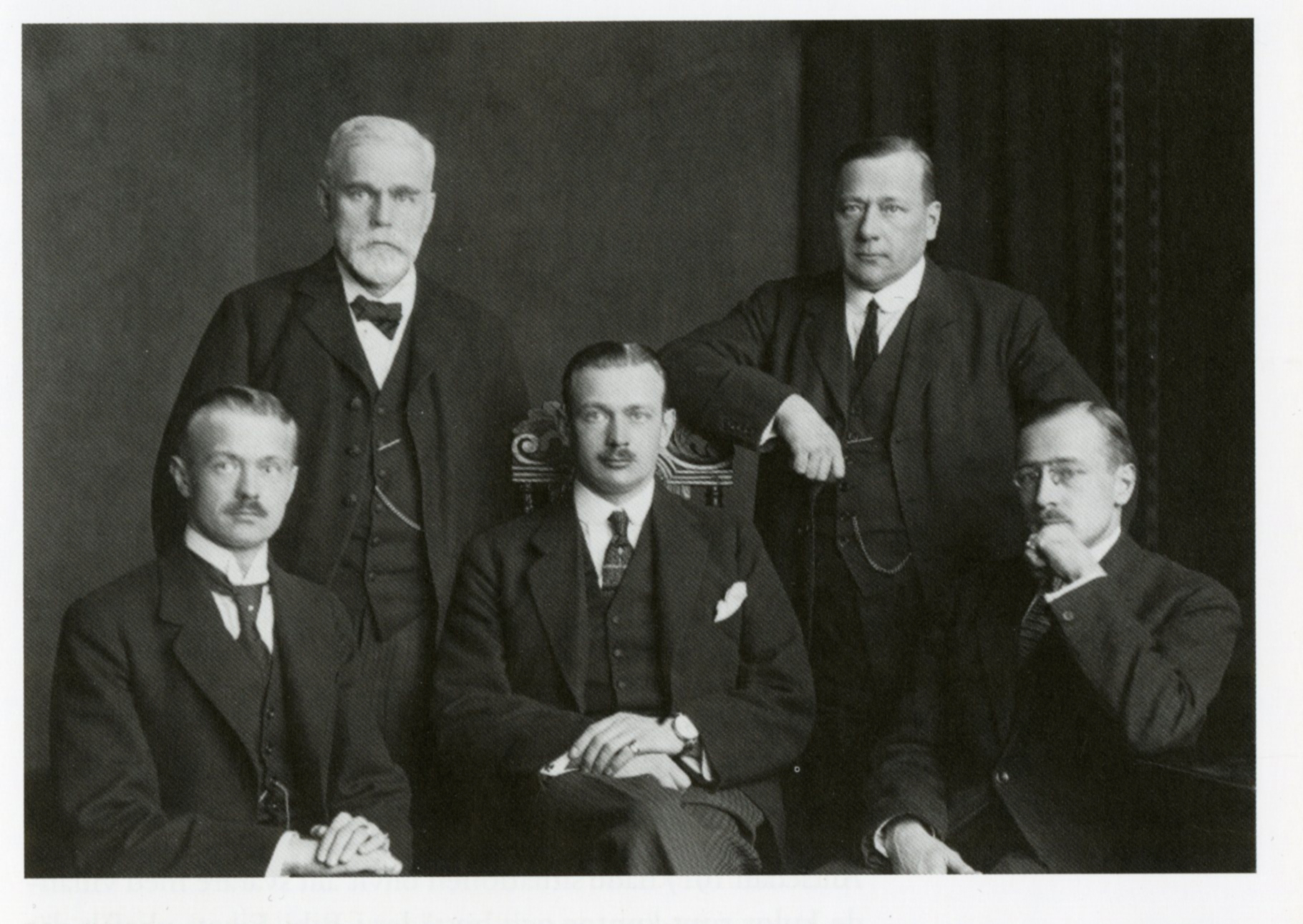

Gösta Nobel was Ludvig Nobel’s youngest son and, at the age of 30, he had to shoulder the role of Managing Director of Branobel at the time of the Russian Revolution. Together with his brother Emil, he tries to save both the companies and the home in St Petersburg, but the brothers are finally forced to make a dramatic escape out of the country.

Gösta was born in 1886 in St Petersburg, and he took over as Branobel’s Managing Director at the time of the Russian Revolution in 1917. He turned out to be the last Managing Director of the company. His brother Emil, who was a year older, was then head of the machine-building factory and Alfa-Nobel, which sold and repaired Alfa-Laval’s cream separators. In summer 1918, their considerably older brother Emanuel Nobel was at the spa in Jessentuki in north Caucasus while the two younger brothers Gösta and Emil were trying to save Nobel’s assets in St Petersburg.

Gösta was called to a meeting in Moscow with the new Soviet Government’s central oil committee. The Bolsheviks intended to write a constitution for the oil industry that meant that the State would become the new owner with the old owners as ‘technical advisers’ responsible for operation and deliveries to the State. According to Gösta, one participant at the meeting describes the whole thing as a farce: ”They are asking us to arrange a fourth-class funeral – a funeral to which the corpse has to drive its own hearse. ”All the representatives for the oil industry refused to agree to the Bolshevik’s proposals.

On 30 November 1918, the two brothers were detained at the breakfast table by the Secret Police, the Cheka, and accused of ensuring that an employee at Branobel, Mandelstam, had been detained by the English in Baku. The brothers were put in front of the notorious and feared Commissar Varvara Jakovleva-Sternberg who declared that Gösta and Emil would receive the same sentence as Mandelstam – freedom or death. They were imprisoned but, following negotiations, they were freed on condition that they promised not to escape – which they did. On a train in a pitch-dark compartment filled with Red Guards, they got off at a station where two sledges were waiting for them. After a twenty-kilometre journey, they arrived at a farm cottage where they spent the night.

When Gösta saw the ditch that marked the border between Russia and Finland, he later said, ‘For the first time, I understood the true meaning of a border. For me, one side meant probable death, the other, in any case, freedom.

On the edge of the forest, they were suddenly seized by two Finnish border soldiers who took them to the poorest cottage they had ever seen. There, they were given a horse and cart and made their way to the Finnish border by Systerbäck. In Viborg, they then met a large number of Russian refugees.

On 22 December 1918, they arrived in Stockholm where the whole Nobel clan gathered to celebrate Christmas together with Ludvig Nobel’s widow Edla who was just over 70 and was the clan’s central figure.

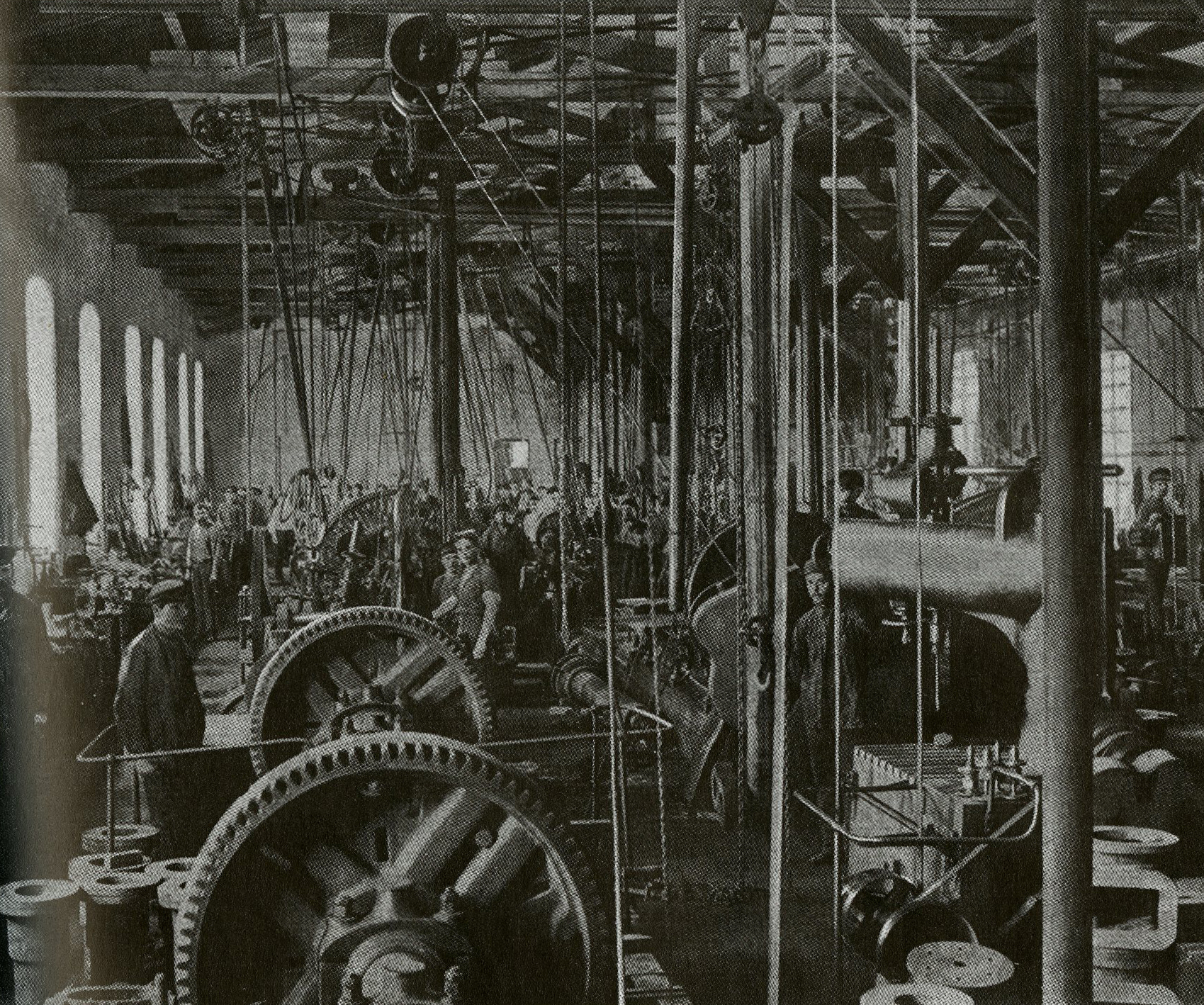

An industrial empire had been lost, not just the oil company and the machine-building factory but also assets in a number of companies in which they were part owners, companies in oil extraction and production, depots and tankers, shipping companies and oilfields.

In February 1919, Gösta Nobel travelled to England to discuss the S.A.I.C. with the British Government. Gösta saw a partner in Standard Oil of New Jersey, which bought eleven exploration permits at drilling fields in Azerbaijan in 1919. The time had come for a merger. After negotiations and a survey in Baku, Standard Oil bought half of Branobel’s shares. When the American Government later entered into negotiations with the Soviet regime on seized assets, Branobel, with its new partner Standard Oil, made up a tenth of the value.

Despite huge losses, the Nobels still had holdings and companies left in, among other places, Finland, the Baltic States and Poland. The family and remaining employees tried to keep the business operations in Europe going, but after Emil’s death in 1951 and Gösta’s in 1955, Branobel was liquidated in Stockholm in 1969.