After the Russian Revolution and his return to Sweden, the young Swedish engineer Anton Carlsund writes down his memories of his work at Ludvig Nobel’s engineering works in St Petersburg. Through his reports, we find out, among other things, that it was orders from the Russian army that laid the foundation for Nobel’s successes and travelling on the ”Nobel wheel” was all the rage in St Petersburg.

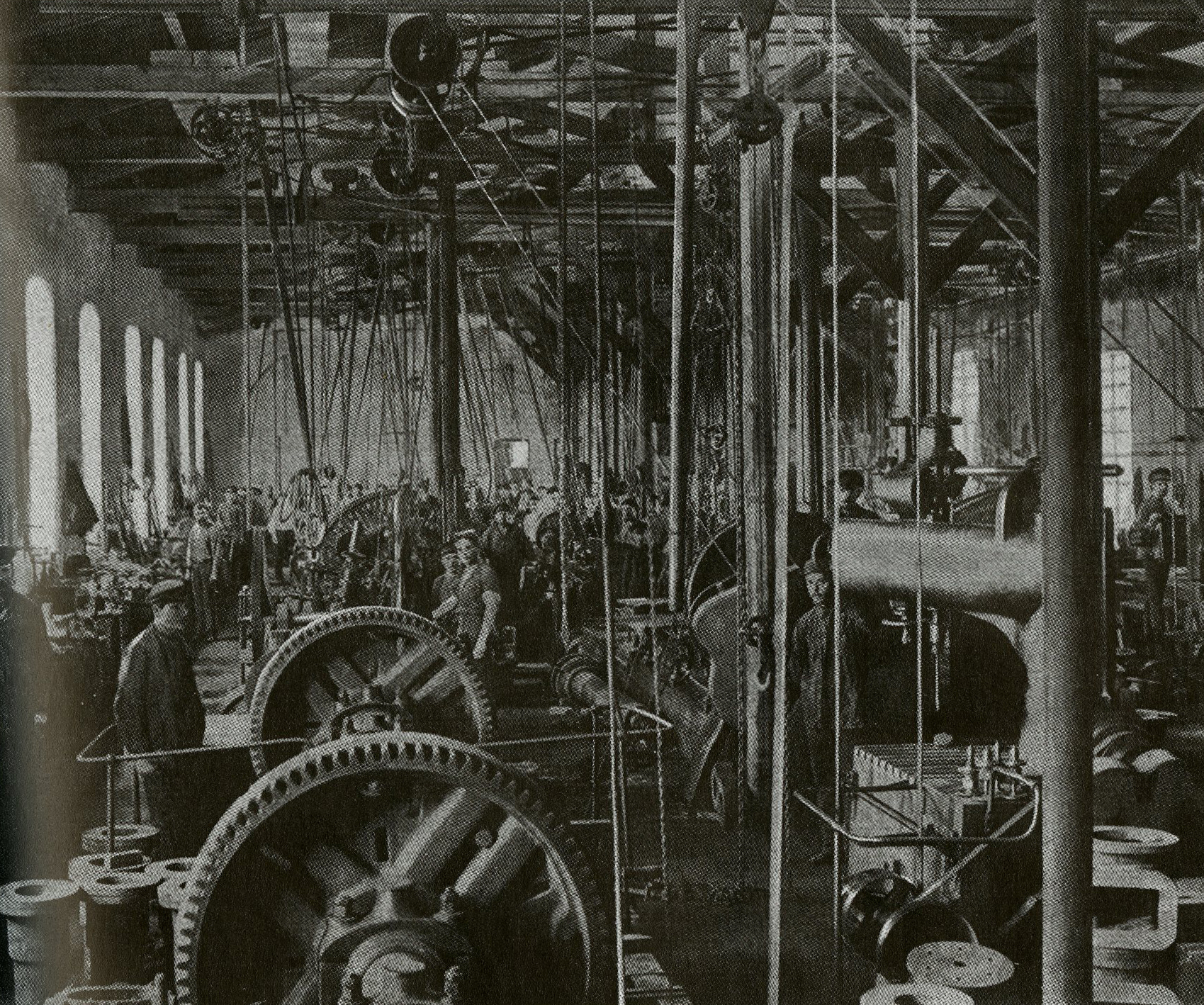

Anton Carlsund was employed in 1892 as a young designer at the Engineering Works of Ludvig Nobel in St Petersburg. At that time, Ludvig Nobel had been leasing a factory on the river Neva, east of St Petersburg, from the Englishman, Ischerwood, since 1862. At the factory, there was a foundry, an engineering workshop and a dock for repairing small vessels. After a few years, he bought a factory whose meticulous manufacturing of pig iron and bronze, castings for heating pipes, water outlets, cranes and accessories gave it a good reputation.

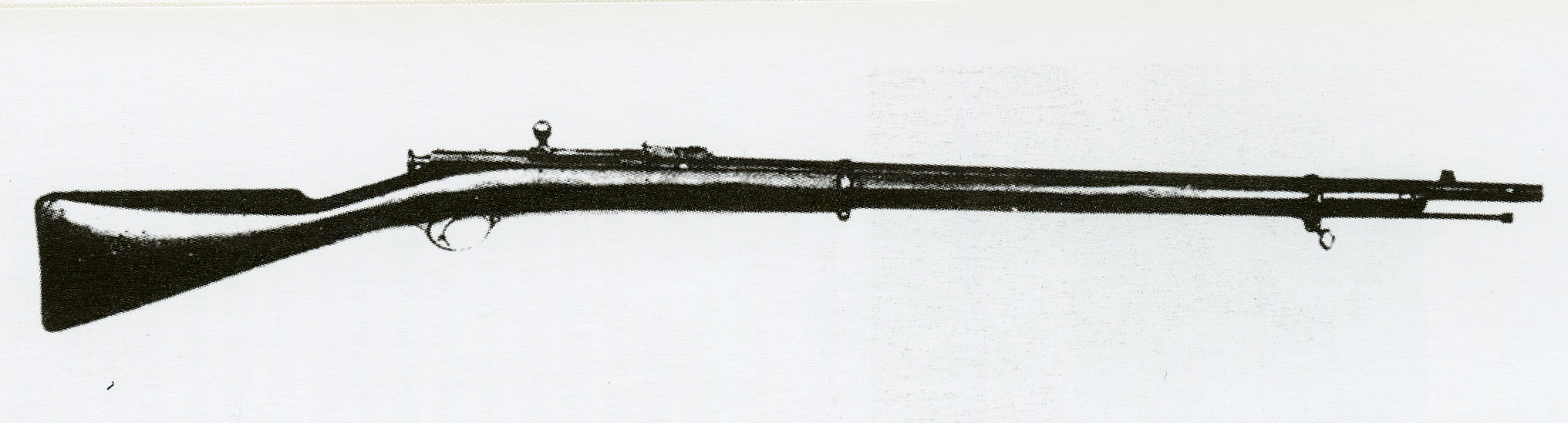

In 1864, the factory received an order for 63,000 iron mines from the Russian artillery administration. It was this order that laid the foundation for the Nobel company’s economic success. During the following years, up to 1870, the artillery also ordered chilled pig iron shells, gun carriages and quick-firing cannons. Nobel later received a further order to reconstruct 100,000 muzzle-loaders for breech-loaders in accordance with systems called Carlé and Krink. The factory’s new machinery, which made channels in the rifle barrels was later to be used at other factories.

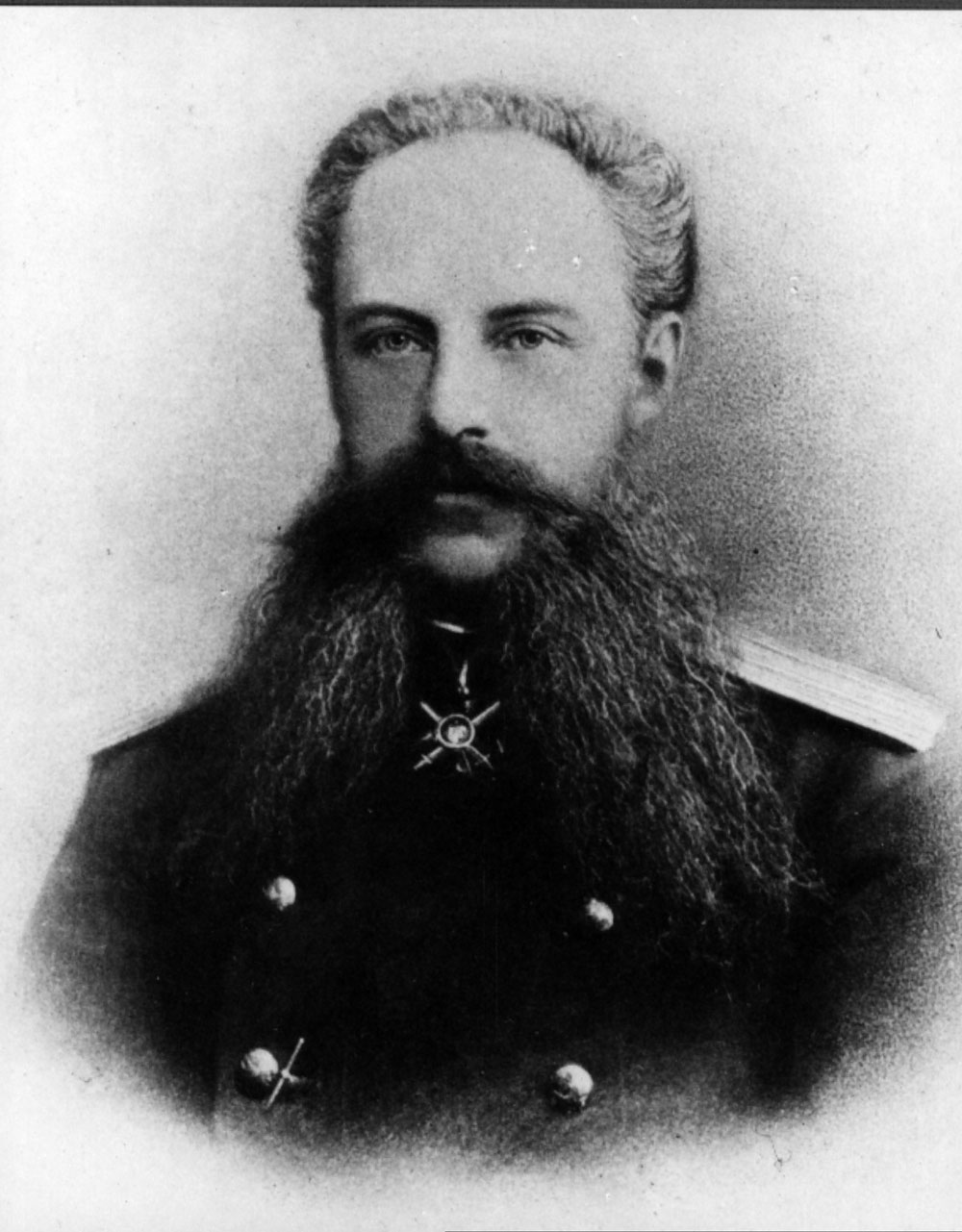

During the Franco-German War in 1870 – 1871, it was time for new arms for the Russian army. The Russian state assigned its factories in Izhevsk, beyond the Urals, on lease to Ludvig Nobel and General P A Bilderling, a prominent specialist in the area of weaponry, for the manufacture of 200,000 rifles. Ludvig Nobel sent materials and his best workers to Izhevsk, where new factories and housing were built. The workers were trained in new working methods and Ludvig’s ability to lead people and solve technical and commercial problems led to success. By the time the factories were handed back to the Russian state in 1878, they had delivered 450,000 new rifles of the Berdanka type.

At the factory on the Neva the manufacture of 100 pieces of the Gatling quick-firing guns and 80 pieces of lighter models with gun carriages was resumed in 1870. These works were performed according to the principle of replaceable parts, which made great demands on both labour management and precision. Nobel often selected their technical assistants from among Finns and Swedes.

At the time of the Russo-Turkish War in 1877 – 1878, the manufacturing of shells was also resumed, including 200,000 four-pound fragmentation grenades, 500 eight-inch and 500 fourteen-inch missiles. There subsequently followed several orders for, among other things, mescher shells and a great number of field gun carriages with the Engelhart system.

For peaceful purposes, working machines like lathes, planing-machines, hydraulic presses, drawbenches, steam hammers, water turbines, retorts for furnaces etc. were manufactured. The Russian army ordered a distillation works with a capacity for 185,000 litres of salt water a day and the plant was in position when the troops landed in Turkmenistan to subdue tribes in the steppes area around Aschabad.

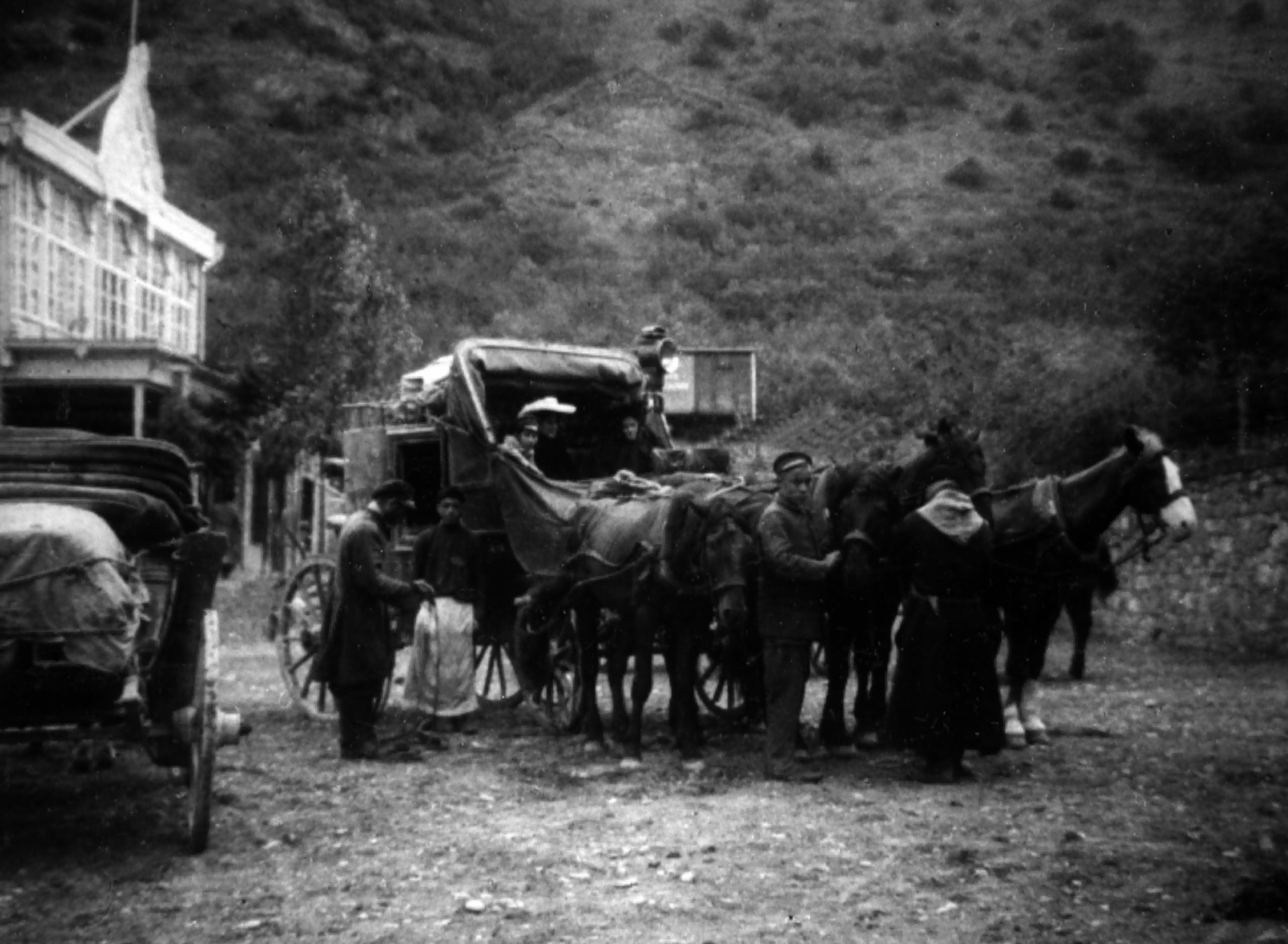

The workshop on the Neva made carriage axles and wheels for carriages drawn by Orloff horses, suitable for Russia’s poor roads. For a while, it was all the rage to travel by ”Nobel wheel” with its rubber tyre and steel spokes. By as early as 1865, manufacturing had been organised according to modern principles and Russia was, therefore, self sufficient in wheels and axles through Ludvig Nobel’s engineering works.

In the workshop, axle and wheel manufacturing became an important section: almost independent from the factory’s other business. Nobel’s hubs, so-called patent wheel guns, which were hermetically sealed against dust and grit, were manufactured in great quantities. In the last decade of the 19th century and first of the 20th century, the factory manufactured torpedo tubes and, from 1894 – 1912, lighting trailers were made for the army. In 1912, the factory was transformed into a limited company and the times changed.

After Ludvig Nobel’s death in March 1888, the factory was managed by his sons, Carl, Emanuel, Emil, Ludvig Jr. and Rolf in that order until it was nationalised in 1918.

(more info)

(more info)

(more info)

(more info)