Visiting German engineering exhibitions, a Swedish employee of the Nobel Company in Russia, Anton Carlsund, saw an early version of the engine that Rudolf Diesel had invented. Via Carlsund, Nobel owned companies in Russia and Sweden took an active part in refining the diesel engine into a practically functioning power source.

Anton Carlsund became interested in Diesel’s engine in conjunction with his visit to an annual meeting of German engineers in Kassel in the late 1890s. On his return to St. Petersburg, he suggested to Emanuel Nobel that he should acquire a patent. Emanuel Nobel was not a technician, but took interest in new inventions.

In Germany, experts discussed intensely the possibility to run engines at such a high pressure. Diesel´s patent was under questioning as it did not quite follow the drawings of the patent. Inventors began appearing at court proceedings, arguing against his patent.

Anton Carlsund inspected the engine in Kassel together with a Professor von Döpp from St. Petersburg and Emanuel Nobel begun negotiations with Diesel. Perhaps Emanuel Nobel was the first to suggest experiments with heavy oils. He realized what the diesel engine would imply for the factory in St. Petersburg and the petroleum production in Baku.

The first meeting with Diesel, and the cautious Emanuel and the vibrant Swedish financier Marcus Wallenberg took place on February 14, 1898. Nobel was a careful man who acted with dignity, Rudolf´s son Eugen Diesel writes. Slowly Rudolf Diesel warmed him up. On February 16, 1898, Emanuel Nobel signed the contract with Diesel, paying 800 000 Mark. “The cool Swede is now more on fire than me for my engine”, Rudolf Diesel writes to his wife. Of the 800 000, 600 000 was paid in cash and 200 000 Mark for shares in the newly established Russische Dieselmotor Co., Nürnberg, which would grant Russian licenses and look into the interests of the companies.

Wallenberg, who had hinted about a future Nobel Prize for Diesel, founded within a short period of time the Sickla Dieselmotorer A.B. in Stockholm.

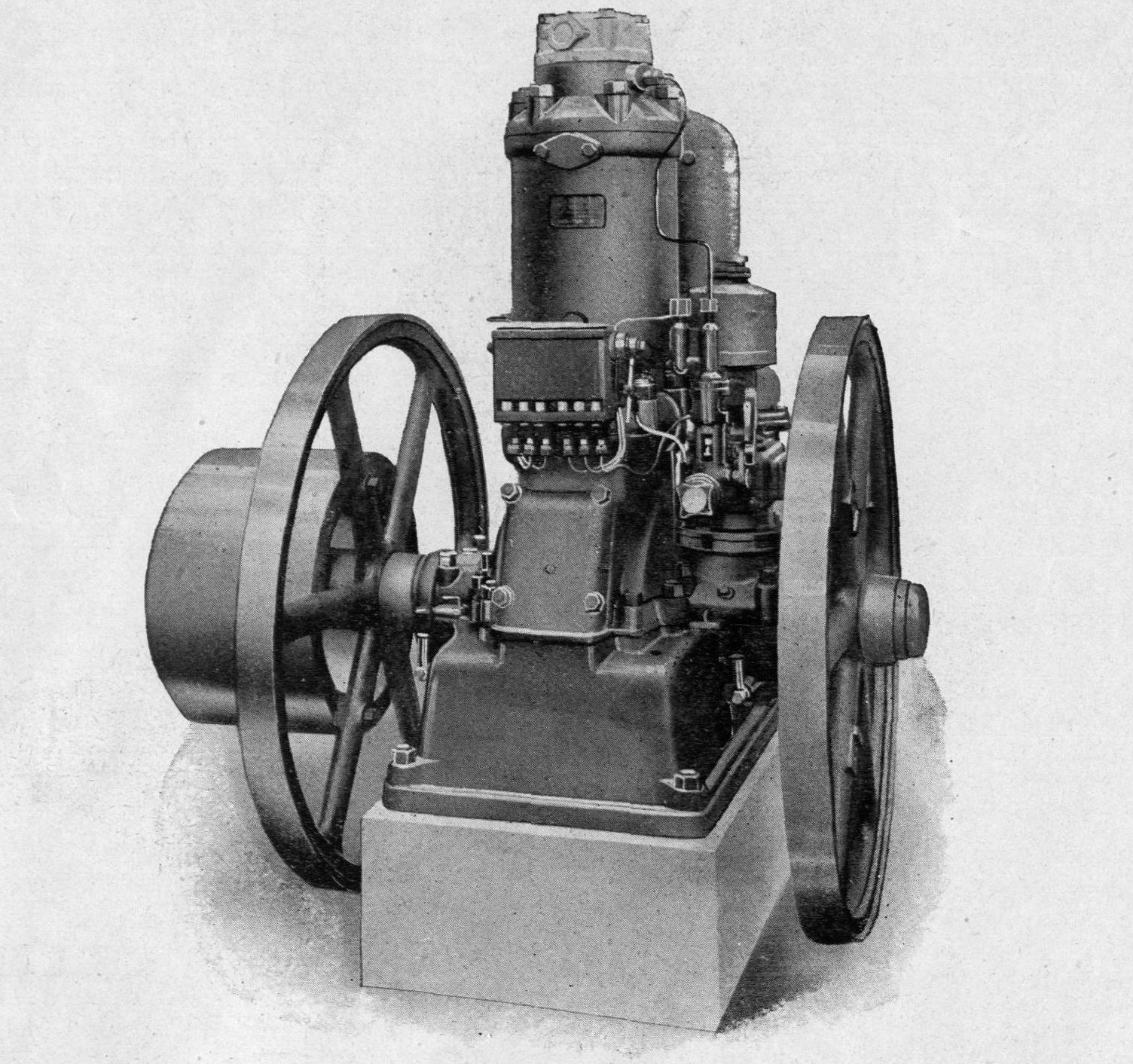

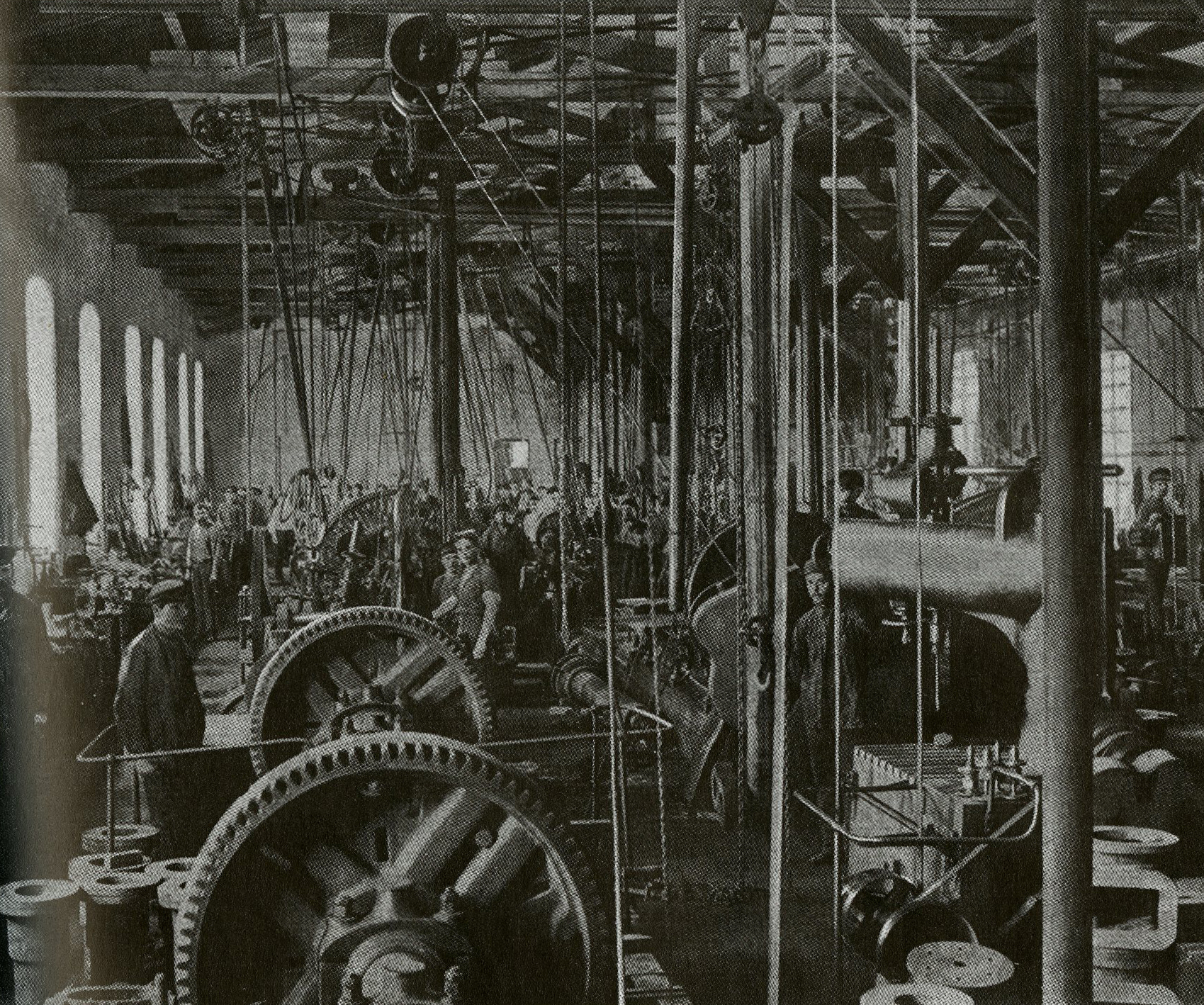

The Mechanical Factory Ludwig Nobel began constructing a new engine of 20 hp. according to Diesel´s drawings, but stopped as it was evident that some details were unsuitable. Anton Carlsund and his staff rebuilt the engine completely. And this new version worked excellently! Eugen Diesel writes that “in the year of 1899, an enthusiastic report from St. Petersburg about a successfully working Augsburgs engine reached Rudolf Diesel. The Mechanical Factory Ludwig Nobel understood fully how to build this engine”.

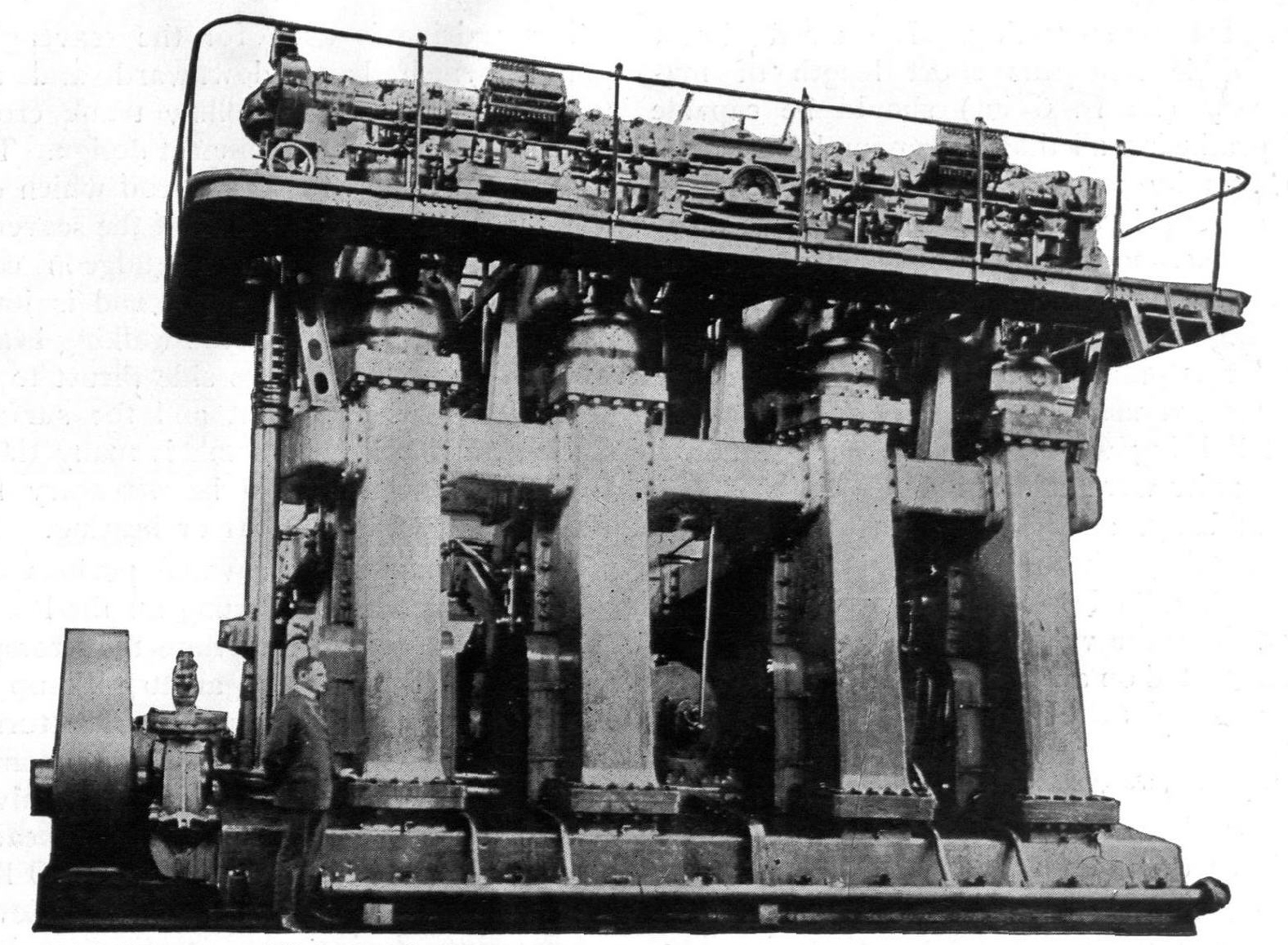

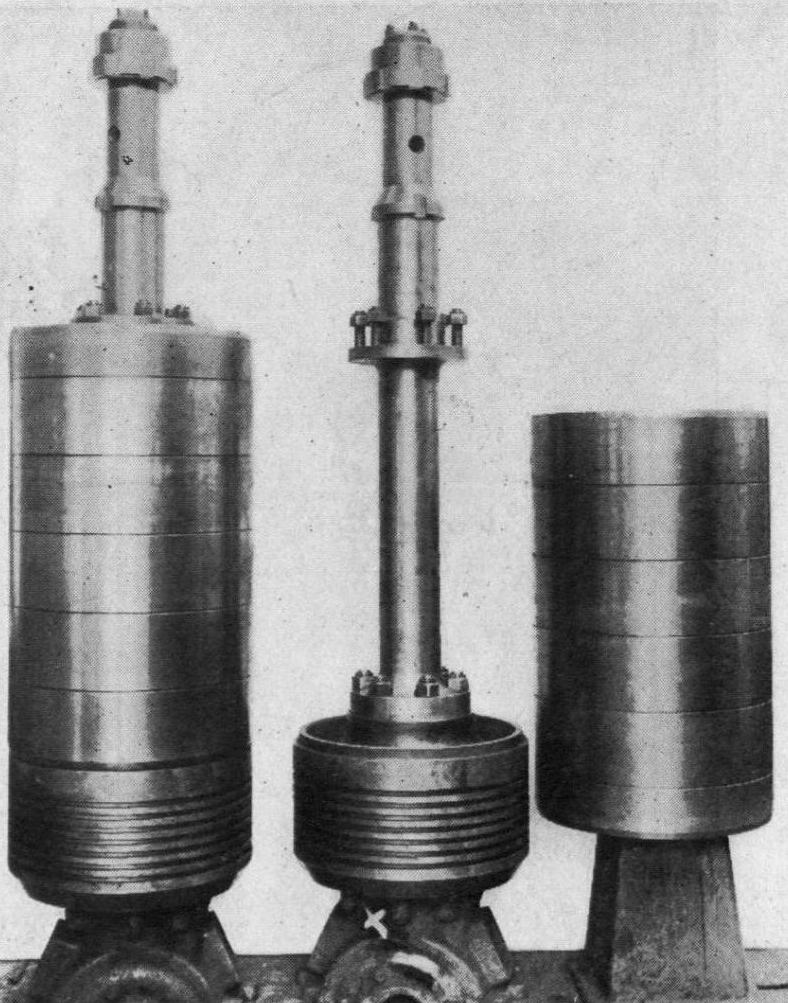

This first engine was a 20 hp. vertical engine with an A-shaped stand and with a cross head connection to the connection rod and crank shaft. The machine was tested officially at the Technical Institute in St. Petersburg. The fuel consumption proved to be 225 gram per horsepower, and the engine worked at a steady pace while producing invisible exhaust gases. Steam engines at the time had fuel consumptions 10 times higher than this Diesel engine.

The factory continued to make more powerful engines, engines of 20 hp. and even 40 hp. in double cylinders, as well as 30 and 60 hp. of the same type. These machines were sold to workshops, to the Russian artillery and the Nobel Brothers Oil Company in Baku. Some teething problems were taken care of as the reputation of the engine grew with increased reliability.

The Augsburg Maschinenfabrik claimed to be responsible for its success. However, the Mechanical Factory Ludwig Nobel had not worked with Augsburg, but much more intensely with Dieselmotorer A.B in Sickla, just outside Stockholm.

In 1899, the young Swede Jonas Hesselman graduated from the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm with an education in the art of building machines and shipbuilding that was considered quite thorough for its time. In February the following year, Jonas was employed at the Dieselmotorer A.B in Sickla.

Simultaneously, as Jonas Hesselman began to work in Sickla, the engineer Ludwig Borggren had graduated at the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, in 1901. He was soon thereafter employed at ASEA in Västerås when he met with Wilhelm Hagelin, manager at the Nobel Brothers Oil Company, visiting Stockholm.

Hagelin informed Borggren of his intention of trying the diesel engine in ships and asked Borggren to find the electrical link between the engine and the propeller. Hagelin imagined the electric propeller motors enclosed in streamlined cases outside the ship to be lowered or raised according to the draft of the ship. Could Borggren help out on this matter? Well yes, he succeeded. Ludwig Borggren arrived in St. Petersburg to begin his new job on January 1st, 1902.

(more info)

(more info)

(more info)