The Swedish engineer, Wilhelm Hagelin, was born in Russia and came to Baku at the end of the 1870s as a stowaway on the river boat. Barely 20 years of age, he started as a filer at Robert Nobel’s paraffin factory and ended up responsible for managing Branobel during the troubled years that heralded the Russian revolution. The new Soviet regime offered him the opportunity to manage the technical operations of the entire oil industry in Baku – but he declined.

Wilhelm Hagelin was born in 1860 in Russia of Swedish parents. His father had worked for the Nobel brothers’ father, Immanuel Nobel, and been a master on river boats on the Volga. In his memoirs, ”37 Years of Happy Working” Wilhelm describes his difficult introduction to working life. After ten months of heavy labour and unfriendly people, he asked a friend of his father, Uncle Hammarström, for a free ticket on the steamer to Baku.

In the spring of 1879, Wilhelm got work as a filer at Robert Nobel’s small paraffin factory in Baku. On his first day at work, Wilhelm describes his first meeting with Robert Nobel, when the latter comes driving through the big factory door. ”He looked into the workshop and caught sight of a new young man. When he heard that I was eighteen and a half years old, he patted me on the shoulder and said: ’Then you must be happy as a sandboy with your whole life ahead of you!’ ”

During the pioneering period, everything went well purely technically, Wilhelm felt, but the expected consumer – the farmer – was reluctant to use the expensive paraffin lamp. Ludvig Nobel then provided paraffin retailers with free lamps and the farmers got a taste for this convenient, inexpensive source of light and consumption increased.

In the autumn of 1879, engineer Alfred Törnqvist returned to Baku after his studies of the oil industry in the USA and began the reconstruction of Robert’s factory. The Swedish-Russian speaking Wilhelm was then given a job as Törnqvist’s writing and calculating assistant. Törnqvist had taken drawings with him from St Petersburg and, together, they made lists of everything that was needed for reconstructing the paraffin factory. Every single nut had to be put down on paper. The lists were sent to Ludvig Nobel’s engineering workshop in St Petersburg where the manufacturing took place.

Wilhelm Hagelin witnessed three blazes that hit Branobel in the years 1880 and 1881. The most serious of these occurred when the tank steamer Nordenskiöld literally exploded while being loaded. Everyone in the engine room died.

Wilhelm lacked an education but saved up the money to study for two years at the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm. Back in Russia, he worked at Branobel’s laboratory in St Petersburg. Wilhelm’s second period in Baku began in 1890. In 1899, he was elected to the board, with responsibility for production and the fleet, which he equipped with diesel engines.

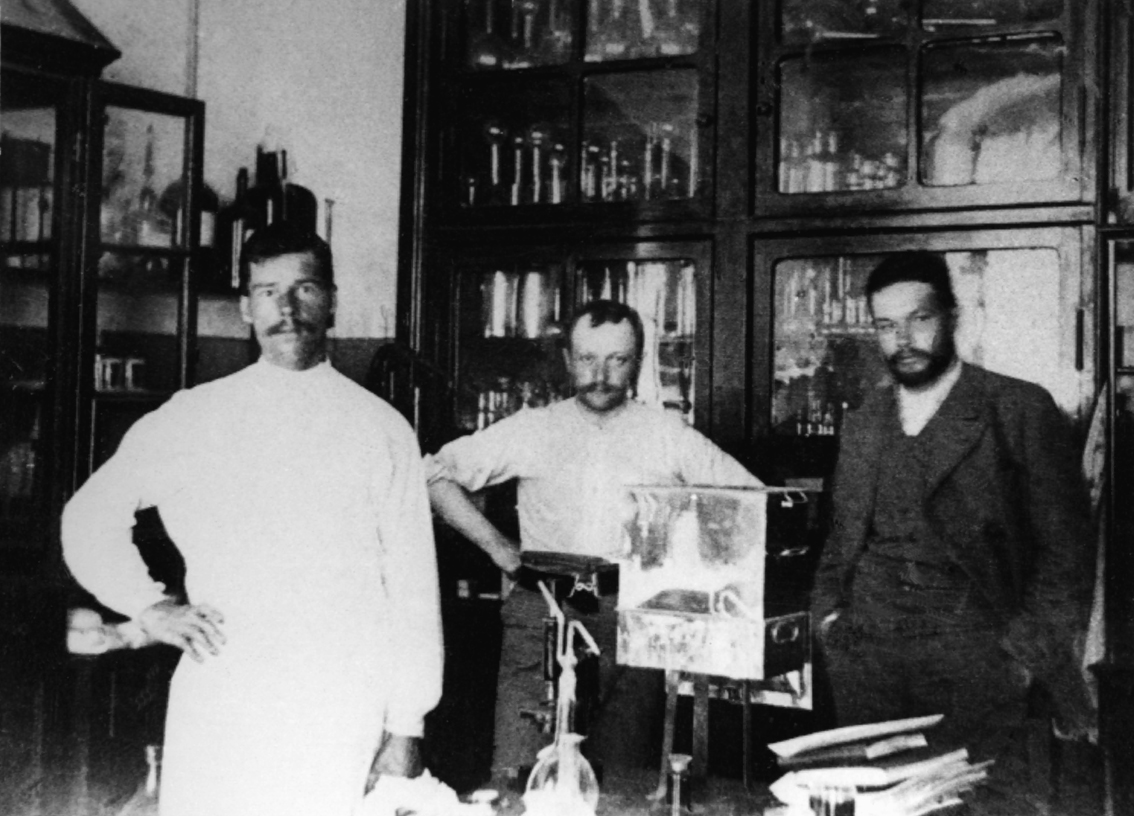

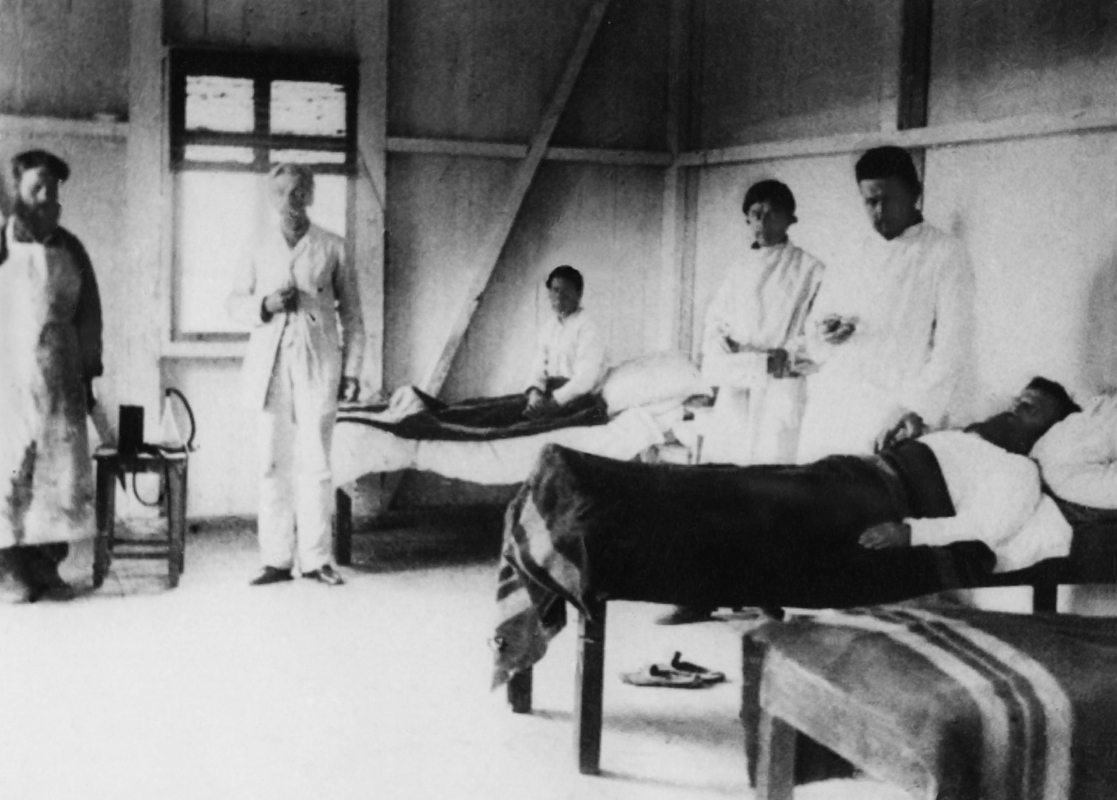

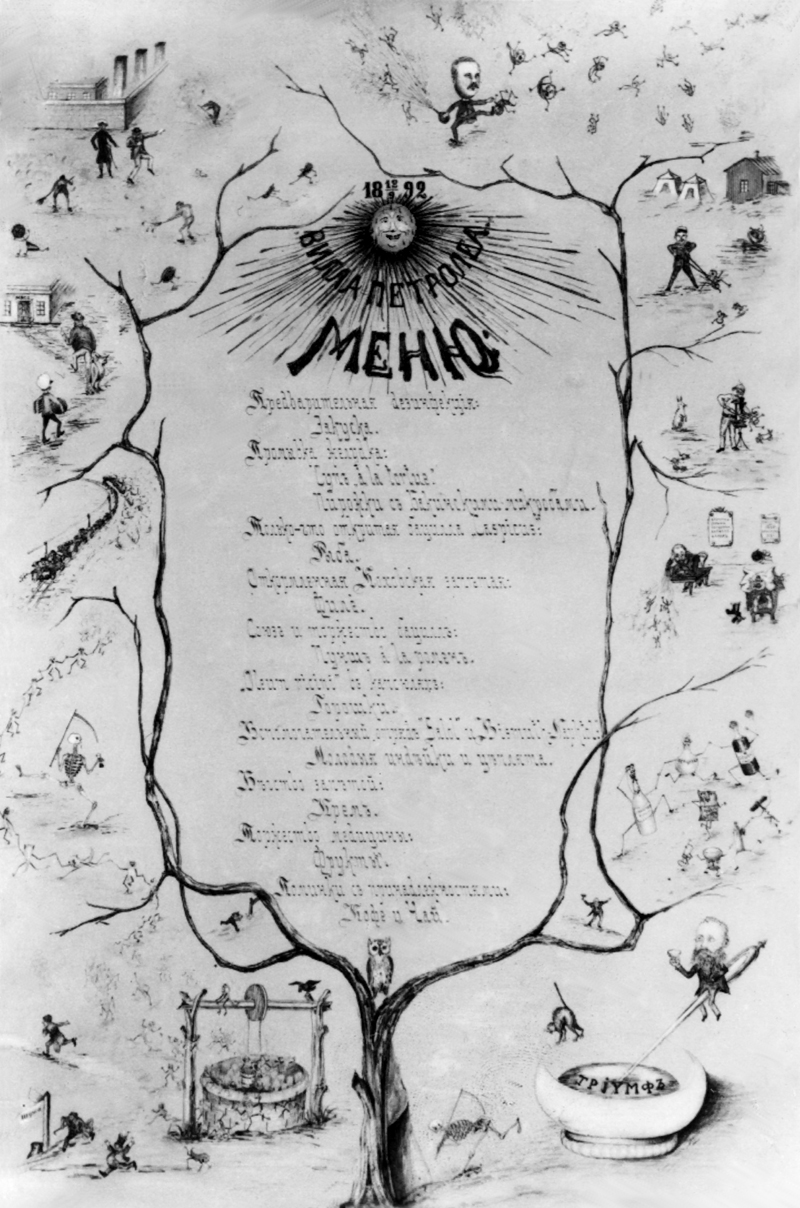

In the summer of 1892, cholera spread to Baku. Emanuel Nobel employed the Russian doctor, Schoubenko, and his American colleague, Blackstein, to fight its spread, together with Wilhelm. Night and day, they inspected the housing and workplaces, ensured that they were kept clean and did not drink water that had not been boiled. These who fell sick were isolated in special cholera barracks. For Branobel, the outcome was 157 cases of illness and about 40 deaths.

In 1903, social disturbances broke out in the southern Caucasus. The strain on Branobel’s management in Baku increased and Wilhelm felt that the head office in St Petersburg was meddling in his work. This took its toll on him and, in the winter of 1905-1906, he decided to leave the company. He was, however, persuaded by Ludvig Nobel’s son Emanuel, to undertake a long trip to the USA instead. Wilhelm’s affection for the company returned during his absence and he returned to Baku to lead the company during the anxious time that heralded the Bolshevik revolution of 1917.

In December 1917, 2,000 oil workers demanded that Branobel’s oil fields be socialised. Wilhelm called for week-long negotiations with workers revolting at the plate factory in Astrakan, north of Baku. In 1918, in St Petersburg, he was asked by a representative of the new power holders if he wanted to take over the technical management of the whole of Baku’s oil industry under the management of Soviet committees. But Wilhelm wondered if he would be listened to and came to the conclusion ”the regime needs other men than me”. He declined and returned to Sweden.

In Stockholm he took part in the work on restructuring the rest of the company and was forced to reluctantly retire at 75 years of age. In 1923, he became an honorary member of the Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences. He makes an appearance as the only ”Nobel” to appear under his own name in Alexis Tolstoy’s novel, ”Naphtha”, which was published in Moscow in 1933.

(more info)

(more info)

(more info)

(more info)